16.1 WHAT CAUSED THE COLD WAR?

The basic cause lay in the differences of principle between the communist states and the capitalist or democratic states which had existed ever since the communists had set up a government in Russia in 1917. Only the need for self-preservation had caused them to sink their differences and as soon as it became clear that the defeat of Germany was only a matter time, both sides, Stalin in particular.

began to plan for the post-war period.

(a) Stalin's foreign policies contributed to the tensions: his aim was to take advantage of the military situation to strengthen Russian influence in Europe; this involved occupying as much of Germany as possible as the Nazi armies collapsed and acquiring as much territory as he could get away with from other states such as Finland, Poland and Rumania.

In this, as will be seen, he was highly successful but the west was alarmed at

what seemed to be Russian aggression.

Was Stalin to blame then for the Cold War? The motives behind Stalin's aims are still a subject of controversy among historians:

(i) Many western historians still believe, as they did at the time, that Stalin was either continuing the traditional expansionist policies of the tsars or, worse still, was determined to

spread communism over as much of the world as possible now that

'socialism in one country' had been established.

(ii) The Russians themselves, and since the mid-1960s some western historians as well, claim that Stalin's motives were purely

defensive: he wanted a wide buffer zone to protect Russia from any further invasion from the capitalist west. There had been much to arouse his suspicions that the USA and Britain were still as keen to destroy communism as they had been at the time of their intervention in the civil war (1918-20): their delay in opening the second front against the Germans in France seemed deliberately calculated to keep most of the pressure on the Russians and bring them to exhaustion. Stalin was not informed about the existence of the atomic bomb until shortly before its use on Japan, and his request that Russia should share in the occupation of Japan was rejected. Above all, the west had the atomic bomb and Russia did not.

Unfortunately it is impossible to be sure which motive was uppermost in Stalin's

mind.

(b) Leading American and British politicians were deeply hostile to the

soviet government as they had been since 1917. Harry S. Truman, who

became US President in April 1945 on the death of Roosevelt, was much

more suspicious of the Russians than Roosevelt who was inclined to trust Stalin. Churchill's views were well known: towards the end of the war he had wanted the British and Americans to make a dash for Berlin before the Russians took it; and in May 1945 he had written in a letter to Truman: 'What is to happen about Russia? Like you I feel deep anxiety ...

an iron curtain is drawn down upon their front.' Both were prepared to take a

hard line.

Historians must try to ignore their own bias and be guided only by the evidence; the conclusion has to be that

both sides were to some extent to blame for the Cold War. If somehow mutual confidence could have been created between the two sides, the conflict might have been avoided, but given their entrenched positions and deep suspicion of each other, perhaps it was inevitable. In this atmosphere almost every international act

could be interpreted in two different ways: what was claimed as necessary for self-defence by one side was taken by the other as evidence of 'aggressive intent, as the events described in the next section show. But at least open war was avoided because the Americans were reluctant to use the atomic bomb again unless attacked directly.

while the Russians dare not risk such an attack.

6.2 HOW DID THE COLD WAR DEVELOP BETWEEN 1945 AND 1953?

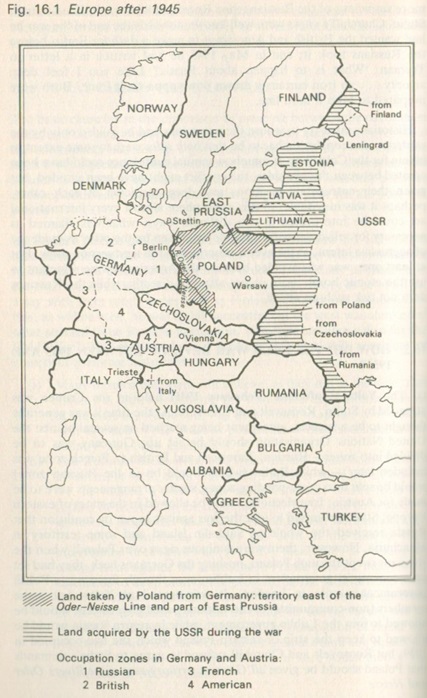

(a) The Yalta Conference (February 1945) held in the Crimea was attended by Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. At the time it was generally thought to be a success, agreement being reached on several points: the United Nations Organisation should be set up; Germany was to be divided into

zones - Russian. American and British (a French zone was included later) - while Berlin (which would be in the Russian zone) would be split into corresponding zones; similar arrangements were to be made for Austria; free elections would be allowed in the states of eastern Europe; Stalin promised to join the war against Japan on condition that Russia received the whole of Sakhalin Island and some territory in Manchuria. However, there were ominous signs over Poland: when the Russians swept through Poland, pushing the Germans back, they had set up a communist government in Lublin, even though there was a Polish government-in-exile in London. It was agreed at Yalta that some members (non-communists) of the London-based government should be allowed to join the Lublin government, while in return Russia would be allowed to keep the strip of eastern Poland which she had occupied in 1939; but Roosevelt and Churchill refused to agree to Stalin's demands that Poland should be given

all German territory east of the Rivers Oder and Neisse.

(b) The Potsdam Conference (July 1945) revealed a distinct cooling off in

relations. The main representatives were Stalin. Truman and Churchill

(replaced by Clement Attlee who became British Prime Minister after Labour's election victory). The war with Germany was over but no agreement was reached about her long-term future beyond what had been decided at Yalta (it was understood that she should be disarmed. the Nazi party disbanded and its leaders tried as 'war criminals'). Moreover Truman and Churchill were annoyed because Germany east of the Oder-Neisse Line had been occupied by Russian troops and was being run by the pro-communist Polish government which expelled some five million Germans living there; this had not been agreed to at Yalta! Truman did not inform Stalin about the nature of the atomic bomb. though Churchill was told about it during the conference. A few days after the conference closed the two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan and the war ended quickly on 10 August without the need for Russian aid (though the Russians declared war on Japan on 8 August and invaded Manchuria).

Though they annexed south Sakhalin as agreed at Yalta they were allowed no part

in the occupation of Japan.

(c) Churchill's 'Iron Curtain' speech (March 1946) was made at Fulton. Missouri (USA) in response to the spread of communism in eastern Europe. By this time pro-communist coalition governments had been established under Russian influence in Poland, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria and Albania. In some cases their opponents were imprisoned or murdered; in Hungary, for example, the Russians allowed free elections and, though the communists won less than 20 per cent of the votes (November 1945), they saw to it that a majority of the cabinet were communists. Repeating the same phrase that he had used earlier Churchill declared: 'From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic on

iron curtain has descended across the continent'; claiming that the Russians were bent on 'indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines', he called for a

western alliance which would stand firm against the communist threat.

The speech helped to widen the rift between east and west: Stalin was able to

denounce Churchill as a warmonger while over a hundred British Labour MPs signed

a motion criticising the Conservative leader; but he was only expressing what

most leading American politi¬cians felt.

(d) Undeterred by the Fulton Speech the Russians continued to tighten their grip on eastern Europe: by the end of 1947 every state in that area with the exception of Czechoslovakia had a fully communist government. Election were rigged, non-communist members of the coalition governments were expelled, many being arrested and executed, and eventually all other political parties were dissolved; all this took place under the watchful eyes of secret police and Russian troops. In addition Stalin treated the

Russian zone of Germany as if it belonged to Russia, allowing only the communist party and draining it of vital resources. (Yugoslavia did not quite fit the pattern: the communist government of

Marshal Tito had been legally elected in 1945. He had immense prestige as a leader of anti-German resistance; it was Tito's forces, not the Russians, who

had liberated Yugoslavia from the Nazi occupation, and Tito resented Russian interference.) The west was profoundly irritated by Russia's attitude, which seemed to disregard Stalin's promise of free elections made at Yalta; the Russians could argue that friendly governments in her neighbouring states were essential for self-defence, that these states had never had democratic governments anyway and that communism would bring much-needed progress to backward countries.

Even Churchill had agreed with Stalin in their 1944 discussions that much of

eastern Europe should be a Russian 'sphere of influence'.

(e) The next major development was the appearance of the 'Truman

Doctrine' which soon became closely associated with the Marshall Plan.

(i) The 'Truman Doctrine' sprang from events in Greece where communists were trying to overthrow the monarchy. British troops, who had helped liberate Greece from the Germans in 1944. had restored the monarchy but were now feeling the strain of supporting it against the communists who were receiving help from Albania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.

Ernest Bevin, the British Foreign Minister, appealed to the USA and Truman

announced (March 1947) that the USA would 'support free peoples who are

resisting subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pres¬sures'.

Greece immediately received massive amounts of arms and other supplies

and by 1949 the communists were defeated.

Turkey, which also seemed under threat, received aid worth about 60 million dollars. Thc 'Truman Doctrine' made it clear that the US had no intention of returning to isolation as she had after the First World War; she was committed to a policy of

containing the spread of communism, not just in Europe but throughout

the world, including Korea and Vietnam.

(ii) The Marshall Plan (announced June 1947) was an economic extension of the 'Truman Doctrine'. American Secretary of State George Marshall produced his

European Recovery Programme (ERP) which offered economic and financial help wherever it was needed. 'Our policy', he declared, 'is directed not against any: country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.' Its aim was to promote the economic recovery of Europe. thus ensuring markets for American exports; in addition,

communism was less likely to gain control in a prosperous western Europe. By September 16 nations (Britain, France, Italy. Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Austria. Switzer¬land, Greece, Turkey, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and the 3 western zones of Germany) had drawn up a joint plan for using American aid; over the next four years over 13,000 million dollars of Marshall Aid flowed into western Europe. fostering the recovery of agriculture and industry which in many countries were in chaos as a result of war devastation. The Russians on the other hand were well aware that there was more to Marshall Aid than benevolence. Although aid was in theory available to eastern Europe, Molotov, the Russian Foreign Minister, denounced the whole idea as 'dollar imperialism', seeing it as a blatant American device for gaining control of western Europe - and, worse still. for interfering in eastern Europe, which Stalin considered to be in the Russian 'sphere of influence'. Russia rejected the offer and neither her satellite states nor Czechoslovakia, which was showing interest, were allowed to take advantage of it.

The 'iron curtain' seemed a reality and the next development only served to

strengthen it.

(f) The Cominform was set up by Stalin (September 1947). This was an organisation to draw together the various European communist parties. All the satellite states were members and the French and Italian communist parties were represented. Stalin's aim was to tighten his grip on the satellites: to be communist was not enough; it must be

Russian-style communism. Eastern Europe was to be industrialised, collectivised and centralised; states were expected to trade primarily with Cominform members and all contacts with non-communist countries were discour¬aged. Only Yugoslavia objected, and was consequently expelled from the Cominform in 1948, though she remained communist. In 1949 the

Molotov Plan was introduced, offering Russian aid to the satellites,

and another organisation known as Comecon (Council of Mutual Economic

Assistance) was set up to co-ordinate their economic policies.

(g) The communist takeover in Czechoslovakia (February 1948)

came as a great blow to the western bloc, because it was the only remaining democratic state in eastern Europe. There was a coalition government freely elected in 1946. The communists had won 38 per cent of the votes and held a third of the cabinet posts. The Prime Minister. Klement Gottwald, was a communist; President Bend and Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk were not, and they hoped that Czechoslovakia with its highly developed industries would remain as

a bridge between east and west. However, a crisis arose early in 1948. Elections were due in May and all the signs were that the communists would lose ground: they were blamed for the Czech rejection of Marshall Aid which might have alleviated the continuing food shortages. The communists decided to act before the elections; already in control of the unions and the police, they seized power in an armed coup, while thousands of armed workers paraded through Prague. All non-communist ministers, with the exception of Bend and Masaryk, resigned. A few days later Masaryk's body was found under the windows of his offices; his death was described officially as suicide, but Dubcek's opening of the archives in 1968 proved it was murder. The elections were duly held in May but there was only a single list of candidates - all communists. Benet resigned and Gottwald became President. The western powers and the UN protested but could hardly take any action because they could not prove Russian involvement: the coup was purely an internal affair. However, there can be little doubt that Stalin, disapproving of Czech

connections with the west and of their interest in Marshall Aid, had prodded the Czech communists into action: nor was it just coincidence that several of the Russian divisions occupying Austria were moved up to the Czech frontier.

The bridge between east and west was gone: the 'iron curtain' was complete.

(h) The Berlin blockade and airlift (June 1948-May 1949) brought the Cold War to its first climax. The crisis arose out of disagreements over the treatment of

Germany:

(i) At the end of the war, as agreed at Yalta and Potsdam. Germany and Berlin were each

divided into four zones. While the three western powers set about organising the economic and political recovery of their zones, Stalin. determined to make the Germans pay for the damage inflicted on Russia, continued to treat his zone as a

satellite, draining its resources away to Russia.

(ii) Early in 1948 the three western zones were merged to form a single economic unit whose prosperity. thanks to Marshall Aid. was in marked contrast to the poverty of the Russian zone. At the same time the west began to prepare a constitution for a self-governing West Germany. since the Russians had no intention of allowing complete German reunification.

However, the Russians were alarmed at the prospect of a strong independent West

Germany which would be part of the American bloc.

(iii) When in June 1948 the west introduced a new currency and ended price controls and rationing in their zone and in West Berlin, the Russians decided that the situation in Berlin had become im¬possible.

Already irritated by the island of capitalism deep in the communist zone, they

felt it impossible to have two different currencies in the same city and were

embarrassed by the contrast between the prosperity of West Berlin and the

poverty of the surrounding area.

The Russian response was immediate: all road, rail and canal links between West Berlin and West Germany were closed: their aim was to force the west to withdraw from West Berlin by reducing it to starvation point. The western powers. convinced that a retreat would be the prelude to a Russian attack on West Germany, were determined to hold on; they decided to fly supplies in, rightly judging that the Russians would not risk shooting down the transport planes. Over the next 10 months 2 million tons of supplies were airlifted to the blockaded city in a remarkable operation which kept the 2.5 million West Berliners fed and warmed right through the winter. In May 1949 the Russians admitted failue by lifting the blockade. The affair had important results: the outcome provided a great

psychological boost for the western powers though it brought relations with Russia to their worst ever; it caused the western powers to

co-ordinate their defences by the formation of NATO. In addition it meant that since no compromise seemed possible. Germany was doomed to be

permanently divided.

(i) The formation of NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) took place in April 1949. The Berlin blockade demonstrated the west's military unreadiness and frightened them into making definite prepara¬tions. Already in March 1948 Britain, France, Belgium. Holland and Luxembourg had signed the

Brussels Defence Treaty, promising military collaboration in case of war. Now they were joined by the USA, Canada. Portugal, Denmark, Ireland, Italy and Norway. All signed the North Atlantic Treaty, agreeing to regard an attack on any one of them as an attack on them all, and placing their defence forces under a joint NATO Command Organisation which would co-ordinate the defence of the west. This was a highly significant development: the Americans had abandoned their traditional policy of 'no entangling alliances' and for the first time had pledged themselves in advance to military action.

Predict¬ably Stalin took it as a challenge, and tension remained high,

especially when it became known in September 1949 that the Russians had

developed their own atomic bomb.

(j) The two Germanies. Since there was no prospect of the Russians allowing a united Germany, the western powers went ahead alone and set up the

German Federal Republic, known as West Germany (August 1949). Elections were held and Konrad Adenauer became the first Federal Chancellor. The Russians replied by setting up their zone as the

German Democratic Republic or East Germany (October 1949). Even in the 1980s Germany remains divided, and it was difficult to imagine the circumstances in which she could become united again.

|

|