|

|

|

1. MOROCCO | |

Algeciras ConferenceThe first testing-ground of the European alignments was Morocco. France, by her agreements with Italy in 1902 and with Britain in 1904, had been promised that these two Powers would not interfere with the furthering of French interests in Morocco. Important though this would be for both France and Morocco, it had still wider implications. Morocco was the last North African territory to come under the controlling influence of a European Power: Egypt was a British `sphere of influence'; Italy had secured a free hand in Tripoli; Tunis and Algeria were French territories; and now France was to be allowed to concern herself in Morocco which hitherto had been an independent Mohammedan State. There would thus be no room for any other European Power to squeeze into Mediterranean Africa. Germany particularly resented being thus shut out. What concerned her even more than the commercial gains to her competitors was what she regarded as the loss of prestige through being ignored in the scramble for North Africa. Moreover, the advantage had gone to her political rival France and to the latter's new friends Italy and Britain. German resentment was expressed in typical fashion by Kaiser William II who in March 1905 landed at the Moroccan port, Tangier, where he delivered an angry speech in which he congratulated the Moroccan Sultan upon his independence and assured him of German support in maintaining it. Though this claim of Moroccan independence may have been politically correct, the Kaiser's method and timing in asserting it was a deliberate and public challenge to France. French public opinion boiled with indignation, its mouthpiece being Delcasse who was prepared to go to all lengths in order to rebut German interference. But the French Government knew that there were limits beyond which it could not go with safety. Its ally Russia, recently beaten by Japan, was in no condition to offer support; nor had France any claim to military support from Britain. Moreover, Italy, having a foot iii both alliances, could not be relied upon in an emergency. Thus t lie French Government had to decide whether, in the last resort, it could afford to risk being isolated in a conflict with Germany, and perhaps also with Austria, for the sake of pushing French interests in Morocco. The Government therefore yielded to German pressure: Delcasse, who personified the antagonism towards Germany, was dismissed from office, and France agreed to the holding of an international conference to decide the status of Morocco. In April 1906 the Conference assembled at Algeciras in southern Spain. It looked as though Germany had won the first round of her contest with France, but events at the Conference showed that she had over-reached herself. Instead of being overawed by Germany's aggressiveness, the other Powers held together to resist her claims. Of the twelve members of the Conference, the only once to support Germany was her ally Austria-Hungary. The other leading Powers - Britain, Russia, Italy, Spain, and the U.S.A. - all were pro-French, and the other members followed this lead. Two questions were on the Conference agenda, namely, Moroccan finance and public order. The first was settled by establishing an international bank which was to be controlled by the Bank of I England, the Bank of France, the Bank of Spain, and the German Imperial Bank. This would mean that, in the event of disputes About financial policy, the Germans would be outvoted by the other three. The policing of Morocco was to be carried out jointly by France and Spain - to the exclusion of Germany. Thus France by her moderation gained more than if she had adopted the aggressive policy of Delcasse. Germany had suffered a major diplomatic set-back. In face of this there were two alternative policies that she might adopt. Either she could try to allay European fears by a more moderate and peaceable attitude, or she could equip herself until she was strong enough to dominate Europe and recover the prestige that she had lost. With William II in command, moderation was impossible. He burned with a desire to give to Germany `a place in the sun'.

|

|

Naval RivalryThe point at which, in the Kaiser's view, German equipment most urgently needed strengthening was the navy. We have seen already the beginning of this process in the German Navy Laws of 1900. Britain, unable to ignore the implied threat to her security, in 1905 laid down the Dreadnought, the first of a new class of super-battleships. Inevitably Germany followed suit. So a naval rivalry began, and as it went on it gathered momentum. The British aim was to maintain a navy equal to any two other navies in the world. In 1908 she began to build super-Dreadnoughts; and by this time the British electorate was so clamant for the supremacy of the Royal Navy that there was a popular slogan: `We want eight, and we won't wait.' This was in response to a proposal to slow up the construction of the new, and costly, super-Dreadnought class of battleships. In addition to enlarging the navy and re-equipping it, the British also re-deployed it. If the German challenge to Britain's supremacy at sea ever brought an open clash, it was likely to come in the North Sea or the Channel. In 1904, therefore, Admiral Lord Fisher reinforced his fleets in the Atlantic and the Channel by deliberately weakening the Mediterranean fleet based on Malta. This had become possible because, since the Entente settlement, the British and French Navies could co-operate, and the French could be entrusted largely with the defence of the Mediterranean. This arrangement contributed much to Anglo-French superiority at sea when hostilities broke out in 1914.

|

|

The Entente TightensThe new naval arrangements also had the effect of drawing the Entente Powers more closely together and of making Germany more nervous about her own security. A further tightening of the Entente was shown in an AngloRussian treaty of 1907. Like the 1904 agreement between Britain and France, this was in no sense a military alliance. It related only to certain territories in Asia. For a long time Britain had been suspicious of Russian moves in the direction of India. The 1907 t treaty went a long way towards restoring confidence. It recognized British interests in Afghanistan, the gateway to India; it guaranteed non-interference in Tibet; and it divided Persia into three zones. c )f these zones the northern and the nearest to Russia was to be a Russian sphere for purposes of trade; the south and east, on the Persian Gulf, was to be under British influence; and between t these was to be neutral territory. This arrangement was in no way to affect the independence of Persia. So far as Europe as a whole was concerned, the significance of these arrangements lay not in their precise terms but in the fact that, for the first time since the Crimean War of 1854-56, Britain lid Russia were on openly friendly terms. Hitherto, while France and Russia had been allies, and France and Britain had been associated in the Entente, there had been no direct link between Britain and Russia. From 1907 the threefold Entente was a fact. I n these circumstances it was natural that Germany should be nervous. She saw herself as the victim of deliberate `encirclement', ringed round by enemies, the only exception being Austria I Hungary. The Kaiser therefore determined to try to break t he circle by challenging his rivals before they became any stronger. Once again it was Morocco that provided the occasion for dispute.

|

|

Agadir Crisis, 1911Almost as soon as the Algeciras settlement had given the French a safe foothold in Morocco they began to extend their control over the country. Claiming that disorder on the Algerian-Moroccan frontier endangered order in Algeria, the French sent troops to occupy Moroccan border villages. What amounted to civil war in Morocco ended in the replacement of the Sultan by his brother. The latter, unable to restore order, applied to the French for help, and early in 1911 a French army was sent to occupy Fez, the capital. Germany, anticipating that this would lead to French annexation of the country, claimed that this was a breach of the Algeciras agreement. As a form of protest, a German gunboat, the Panther, was sent to Agadir, a port on the Moroccan Atlantic coast. The Germans claimed that their object was to protect their nationals in Morocco; but they had so few people and so little property in the country that this was plainly a pretext. Once more there was friction between Germany and France; and other European Powers, fearing that friction might lead to open conflict, began to concern themselves, especially those who had been represented at Algeciras. This time there was no general conference, but negotiations went on to try to find a settlement. Britain made it clear that she would stand firmly by France. Hence Germany, unable to secure the expulsion of the French from Morocco, demanded `compensation' elsewhere in Africa. The upshot, after months of negotiations, was that France obtained Germany's consent to a French Protectorate in Morocco, and France granted to Germany some 100,000 square miles of the French Congo. Thus in the eyes of the world Germany's dignity had been preserved. In reality she had received another severe diplomatic rebuff. Not only was the Congo territory of very little real value, but she had failed completely in her primary objective, namely, to prevent the French control of Morocco. Moreover, once again Germany's diplomatic isolation had been demonstrated plainly. Yet once again, instead of this causing Germany to change either her policy or her methods, it spurred her to increase still further her military and naval strength. Inevitably the result was to increase the mutual suspicion and tension among the nations and to render more and more difficult the peaceful solution of other differences that might

|

|

2. HAGUE CONFERENCESHow to straighten out this diplomatic tangle and to avert a final clash no one seemed able to devise. The only man who made a definite effort to solve the problem was Czar Nicholas II of Russia; and his two efforts showed how unsolvable it was.

|

|

First Conference, 1899As early as 1899 the Czar had the common-sense idea of gathering representatives of the chief Powers to discuss how to limit armaments. He gained enough support for his suggestion to warrant calling a conference. The Dutch capital, The Hague, was decided upon as the meeting-place, and there during May-July 1899 the delegates of twenty-seven States met together. As such a conference was without precedent, the members had to feel their way with some caution. The Russians proposed that for five years each country should agree not to increase its armaments above the existing levels. So mutually suspicious and mistrustful were the nations that even this modest and innocent-looking proposal could not be applied. One practical difficulty was that any particular item of armament had different values to different countries: to Britain a battleship had a high value but to an inland country none at all; and how to equate one item of equipment to another was an unsolvable problem. Thus the whole proposal to limit armaments broke down. Only one achievement of any worth remained to the Conference's credit. This was the setting up of a court of international justice, called the Permanent Court of Arbitration or, more commonly, The Hague Court. To this tribunal the nations agreed to bring their disputes provided that these were such as involved `neither honour nor vital interests'. Even this narrow scope was to have little practical effect: not only was no nation hound to submit a dispute to arbitration, but even when a dispute was submitted the Court had no means of enforcing its decision.

|

|

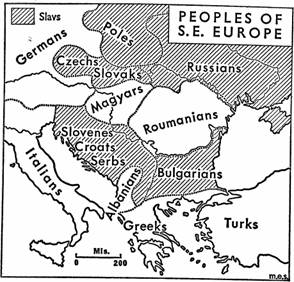

Second Conference, 1907The failure of the 1899 Conference encouraged the conviction that sooner or later war would become inevitable. Hence, every European country, mistrusting its fellows, began to accumulate stocks of weapons and munitions in readiness for whatever danger might lie ahead. So the `armaments race' involved all the Powers. As time passed, the rivalry became more and more intense and the pace quickened, each trying to outdo its rivals. We have seen one aspect of it already in the naval rivalry between Britain and Germany. Before long the financial burden of it threatened to bring ruin upon all alike. Because of these dangers, in 1907 a second Conference met at The Hague. Since the previous Conference the international situation had worsened seriously, and the representatives met in an atmosphere of mistrust. Any attempt to limit armaments was soon abandoned as hopeless, and all that was achieved was an effort to make the next war more 'humane': unfortified towns were not to be bombed; rules were agreed upon for the treatment of prisoners of war; and so on. This second demonstration that apparently war was inevitable was an incentive to still more feverish preparations for it by all the Powers. The great Continental Powers increased their armies, and Britain continued to strengthen her navy which was her first line of defence. The only remaining question seemed to be just when and where war would break out. Because all the major Powers belonged either to the Triple Alliance or to the Triple Entente, any dispute involving any one of them or of their smaller satellite States would involve them all. The most dangerous area of Europe, in this respect, was the Balkans. There, as we have seen, Russia and Austria had conflicting interests, and there nationalism more strongly than anywhere else was a motive for strife.

|

|

3. BALKAN WARS, 1912, 1913

|

|

Turco-Italian War, 1911-12We have seen that the inauguration of the Young Turk regime in 1908* had been the indirect cause of Austria's annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and so had sparked off a crisis in the Balkans. These two provinces adjoined Serbia's western frontier, they lay on the Dalmatian coast, and their population included a large number of Serbs. For these reasons Serbia had been ambitious to include them in a Greater Serbia. Thwarted in this by Austria's annexation of the two provinces, the Serbs turned for support to Russia, the would-be protector of the Balkan Slavs.

But Russian interference would bring in also Austria's ally, Germany. Moreover if a clash ensued, Russia would not be able to rely upon the support of her allies, Britain and France, since neither of them wished to see Russian influence extended towards the Mediterranean. Russia therefore had to yield. But this did nothing to assuage Serbia's sense of grievance and frustration, and she continued to scheme with the other Balkan peoples so that they could take common action whenever opportunity served. The way for such action was paved by an event outside the Balkans. In 1911 Italy declared war on Turkey and sent an expeditionary force to occupy Tripoli in North Africa. She hoped for an easy conquest without interference by other Powers: already she had secured the assent of France and Britain, and, as Germany and Austria were her allies, they were unlikely to object to the occupation. Also, 1911 was the year of the Agadir crisis, and the other European Powers had too much to occupy their attention to allow themselves to be distracted by relatively unimportant events in Tripoli. In these respects Italy calculated correctly, but she met unexpectedly stubborn resistance from the Turks. One advantage possessed by the Italians was a fleet which could prevent the Turks from sending reinforcements by sea. Nonetheless the Turks, avoiding pitched battles, looked as though they could hold out indefinitely, especially as the Italians were feeling the financial strain of keeping their fleet and armies in the war much longer than they had anticipated. They were saved by the outbreak of war in the Balkans in 1912. This compelled the Turks to make peace. Italy was allowed to keep Tripoli - whose name she changed to the ancient Roman one of Libya - but promised to give back the Dodecanese Islands, which she had seized, as soon as order was completely restored in Libya. As she was always able to claim that there still was some sort of disorder, she retained possession of the islands as well.

|

|

First Balkan War, 1912The connection between the Turco-Italian War and the Balkans was that to Serbia and to other Balkan countries the war in Tripoli was too tempting an opportunity to miss. It made possible a war against Turkey on their own account. Partly as the result of Russian diplomacy and partly owing to the skilled negotiations of the Greek statesman Venizelos, the `Balkan League of Christian States' was formed consisting of Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. Their ostensible objective was to acquire from Turkey better conditions for Macedonian Christians, though their real purpose was to drive the Turks out of Europe altogether, and so to win independence for themselves and the enlargement of their territories. When Turkey refused to yield to their demands, in October 1912 the League declared war. Within a few weeks the League's forces had won a succession of victories so decisive that Turkey was on the verge of complete collapse. At this point, in December 1912, the Powers intervened. The reasons were plain. The maintenance of Turkey in Europe, and especially in Constantinople, was essential as a means of keeping Russia from the Mediterranean and from predominance in the Balkans. There was also the danger that, if Russia decided to intervene actively, the war could no longer be confined to the Balkans, and then no one could predict the end of it. Moreover, if the Balkan League was left to make its own terms with Turkey, the dream of a Greater Serbia could become a reality: presumably she would absorb Albania to the west of her, and so could obtain a long coastline and might grow ultimately into a Mediterranean Power. Such a Serbia could not fail to attract the Serbs from within the Austrian Empire, and no one could estimate how far or with what result disaffection in Austria might then spread. Yet none of the efforts of the Powers could induce Turkey to accept mediation, and the war had to continue, as did also the victorious progress of the Balkan League until in April 1913 its forces were within striking distance of Constantinople itself. In order to save their hold on the city, the Turks then sued for peace. This left the way clear for the European Powers to impose their terms upon all parties in the war. The result was the Treaty of London which had three main provisions. First, Turkey was expelled from Europe except that she was allowed to keep Constantinople and a narrow neck of land to the west of it. Second, the Balkan States were to be allowed to divide among themselves the areas from which Turkey had thus been driven. Third, the only exception to the second provision was that a new State of Albania was formed and this was to remain independent under the rule of a German prince. This third provision was due to Austria's uncompromising insistence. In one respect there was justice in it, for the Albanians were not Serbs and had no wish to be ruled by Serbians. But this was not Austria's real motive: she was concerned to ensure that Serbia should never have a coastline and so to thwart the nationalist ambition for a Greater Serbia to which the Austrian Slavs would be attracted.

|

|

Second Balkan War, 1913Events soon showed that the Treaty of London, instead of settling the Balkan ferment, had only caused it to break out in another direction. Serbia, frustrated in her desire to expand westwards, demanded to be compensated by a large slice of Macedonia. But this was an area which Bulgaria regarded as her rightful share of the spoils. Serbia therefore turned for support to Greece who also had hoped for part of Albania. Serbia and Greece had one advantage over Bulgaria: their troops had been fighting in Macedonia and still were in occupation of the country there, whereas the Bulgars had been fighting mainly in Thrace. Because, therefore, the Serbs and the Greeks held on to what they possessed, the Bulgars attacked in force to drive them out. Thereupon Rumania, who had not been a member of the Balkan League but who now thought she saw a chance also to gain territory at Bulgaria's expense, threw in her lot with Serbia and Greece.

Thus once again the Balkan States were embroiled in war, this time not against their overlord Turkey but among themselves. As might have been expected, Turkey was delighted to watch her enemies squabble among themselves: it gave to her the chance to recover some of what she had lost to them. So Turkey added to Bulgaria's difficulties by re-occupying Adrianople and part of eastern Thrace. Through June and July 1913 the fighting and the accompanying atrocities went on: but at last the Bulgars, beset on every side, had no option but to surrender. The Treaty of Bucharest of August 1913 drew definite boundaries between the Balkan States. Each of the three victors - Serbia, Greece, Rumania - gained considerably at Bulgaria's expense, and Bulgaria thus lost nearly everything in Macedonia. Turkey was allowed to recover Adrianople. Albania remained a separate kingdom.

|

|

Effects of the Balkan WarsThere was some satisfaction in Europe that at last Turkey had been rendered harmless, and that the ambitions of the Balkan States seemed to have been satisfied without their owing dependence upon Russia. Moreover, the disturbances had been confined t o the Balkans without involving the rest of Europe. Unfortunately, events soon showed that Europe had congratulated itself too easily and too soon. The wars and their settlement had left behind I hem active germs of future discontents and strife. Though the great European nations had not taken an active part in the fighting, the effect was to jeopardize the balance of power between them. In general, the prestige of the Central Powers had suffered considerable loss. The Turks had had German arms and advice from German officers, and Turkey had been routed and almost driven out of Europe. The victory and expansion of Serbia were serious set-backs to Austrian policy. Serbia was indeed the pivot of the Balkan situation. The wars had intensified still further the Serbs' antagonism to Austria, and the successes already gained encouraged the hope of more to come. Austria's seizure of Bosnia and her insistence upon an independent Albania, both of which areas cut off Serbia from the sea, were especially resented. After the wars many Serbian army officers engaged in secret terrorist activities against the Austrians. Most important of the terrorist societies was the Black Hand among whose members were many students. Much of this intrigue was known to officials of the Serbian Government, some of whom gave it passive if not active support. It was this intrigue which struck the blow that was to involve all Europe, and almost all the world, in war.

|

|

4. OUTBREAK OF WAR, 1914 |

|

Murder at Sarajevo, 28th June 1914In June 1914 the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, nephew of the Emperor Francis Joseph and heir to the Austrian throne, paid a State visit to Bosnia. He was a liberal-minded man, and there was some reason to hope that when the aged Francis Joseph died - he had been Emperor since the revolutionary year 1848 - a real effort would be made to deal sympathetically with the Slav problem within Austria. But the extreme nationalist elements were too impatient to wait upon events. A visit by the representative of Austrian authority to Bosnia, the country annexed against its will, was a red rag to the nationalist bull. Moreover, 28th June, the day chosen for the Archduke's visit to Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, was St Vitus's day, a Serbian holiday when national feelings among the crowds were likely to run high. The police authorities had warned the Archduke of the impossibility of giving adequate protection, but he insisted on carrying out his programme. Almost inevitably tragedy resulted. As he was leaving the railway station a bomb was thrown at his carriage, but the aim was bad and he was unharmed. Later, as the procession was passing through the town, a conspirator jumped on to the running-board and shot and killed both Francis Ferdinand and his wife. The murderer was a nineteen-year-old student, The resulting situation had explosive possibilities which, however, were tempered because the assassin, being a Bosnian, was :in Austrian subject and not a Serb. Also the murder was committed in an Austrian province. On the face of it, therefore, Austria had no grievance against her Balkan neighbour. But this was not t lie whole story. Prinzip was a member of the Black Hand, which was a Serbian society, and the assassination had been planned and the arms supplied in Serbia. There was strong suspicion that the Serbian Government was implicated in the plot. Though this has never been proved conclusively, some individual members of the Government certainly were aware of it. The diplomatic position thus was that technically Austria had no case against Serbia but that, if she wished to cause trouble, she could so present her grievance as to bring pressure to bear upon Serbia for concessions either political or territorial. In fact, Austria saw the opportunity as being too good to lose. She played her cards astutely. Because any move against Serbia might bring Russia into the quarrel, Austria's first need was to make sure of the attitude of her ally Germany. On 5th July 1914 t lie German Kaiser gave a personal assurance that Austria could rely upon Germany's full support `even if matters went to the Iength of a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia'. To give such a blank cheque before knowing the exact demands that Austria would make upon Serbia was typical of William II's rashness. It was all the encouragement that Austria needed to press her advantage to the full. An opportunity, such as might never recur, had arisen to render Serbia powerless. The Austrian Government proceeded to draw up a series of such demands that Serbia's acceptance of them would virtually end her independence, whereas refusal would involve Serbia in a war that could end only in her extinction. Now that Austria had the whole situation under her own control, she could afford to defer the crisis while she was making plans in the event of war. The general feeling in Europe was that every day that passed made open hostilities less and less likely and the delay tended to lull the Powers into a false sense of security.

|

|

Steps to WarThen on 23rd July Austria suddenly delivered to Serbia ten demands cast in the form of an ultimatum: all the ten had to be conceded within forty-eight hours or war would follow. The chief of the demands were that Serbia should suppress all anti-Austrian propaganda and societies; should remove from the army and civil service all individuals whom Austria would name as obnoxious; should exclude anti-Austrian teachers and books from schools; and should allow Austrian officials to be present in Serbian courts at the trials of those accused of a share in the Sarajevo murders. Within the stipulated forty-eight hours the Serbian Government granted eight of the ten demands and urged that the other two should be submitted to the arbitration of The Hague Tribunal. This submissive reply went almost beyond the limit possible to a nation if it was to retain its independent existence. In spite of this, Austria declared the reply to be unsatisfactory and began to take steps towards the invasion of Serbia. Germany's reaction to the Serbian reply was different. The Kaiser, believing that the reply removed any reason for war, urged Austria to proceed no further. But Austria, still holding the Kaiser's `blank cheque', had no intention of giving way, and made active preparations for hostilities. On 28th July Austria declared war on Serbia, and within twenty-four hours Austrian artillery was bombarding Belgrade the Serbian capital. Even then, Germany urged Austria to be content to limit her operations against Serbia. Events soon were to show that this was a fatuous request. When once the war-machine had been started on its course, it in turn set in motion forces which were completely beyond the control of any one individual or government. Stage by stage, one nation after another became involved until what had begun as a dispute in the Balkans became a general war. The Austrian attack on Serbia left to Russia almost no alternative but to support her Slav satellite. On 29th July the mobilization of Russian forces against Austria-Hungary was ordered, and two days later this became an order for general mobilization. Because of the huge area of Russia, and her lack of good communications, the effective mobilization of her armies was likely to be a slow business. Germany, whose total manpower would be much less than Russia's, must therefore make all speed to put her army on a war footing before the full might of Russia could be assembled. At midnight of 31st July, Germany sent to Russia a twelve-hour ultimatum demanding that Russia should suspend all measures of war. Since this demand was not heeded, on 1st August Germany ordered general mobilization and declared war against Russia. In the meantime France and Britain had been actively concerned. On 31st July Germany inquired about France's attitude in the event of war between Germany and Russia. France refused to commit herself. In fact, France had little choice in the matter: she had a defensive alliance with Russia and, after Germany's declaration of war, she was bound to support her ally. On 1st August France ordered general mobilization, and any hesitation she might still have felt was removed when, on 3rd August, Germany declared war against France.

|

|

BritainBritain's position was the most difficult of all. In the Balkans, the original area of dispute, Britain had no direct interest other than a general wish to prevent Russia's expansion on the Mediterranean - a wish that, considered by itself, might have led her to support Austria. On the other hand, since the formation of the Entente ten years earlier, British foreign policy had been based on t he assumption of friendship with France. As we have seen, joint naval policy had allowed co-operation between the fleets of the two countries. Indeed, Britain's chief concern abroad for some time had been Germany's threat to the Royal Navy's supremacy without which the country's security would be jeopardized. The British people in general had no desire to be involved in war: indeed, the mass of the people scarcely realized the possibility of it. But if Britain, through standing aloof, were to allow France and Russia to be defeated, it was doubtful for how long thereafter she would remain safe, since she then would have forfeited any hope of support from her former friends. What Britain's policy might have been finally, if she had been left with a completely free choice, is difficult to assess. In fact, the turn of events solved the problem for her. There was one respect in which war between Germany and France almost inevitably would concern Britain, namely, its probable infringement of Belgian neutrality. In 1830 the people of Belgium had revolted in order to recover their independence from Holland to which they had been joined by the Treaty of Vienna of 1815. The matter was settled finally by the Treaty of London of 1839: its signatories included Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia. By its terms these Powers not only recognized Belgium's independence but also guaranteed her neutrality and her territorial integrity; that is, they undertook to protect her against all attack. Similar guarantees were given also in respect of the neighbouring State of Luxembourg. In 1870, when war was imminent between Prussia and France, the British Government secured from both Powers a recognition of the terms of the Treaty of London. As a result, Britain remained neutral during the ensuing war. Similarly, on 31st July 1914 Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, asked both France and Germany for guarantees that Belgian neutrality would be respected. France at once gave the required assurance. Germany, however, refused: her excuse was that to do so would reveal, by implication, her plan of campaign. In fact, it had long been known that Germany's strategy was contained in the Schlieffen Plan (to be explained in our next chapter) and that this included a sweep of Germany's armies through Belgium. Germany's refusal to promise that she would respect the terms of the Treaty of London left Britain without any alternative to entering the war to maintain Belgium's neutrality. In so doing, Britain threw in her lot with the Entente in the whole struggle against the Central Powers. The events leading immediately to British intervention were as follows. On 2nd August German troops overran Luxembourg. At the same time Germany demanded permission from Belgium for the movement of troops across her territory into France, promising that Belgian independence would be respected and an indemnity would be paid. Belgium refused this demand and appealed to Britain for support in so doing. On 4th August. German troops invaded Belgium; and on the same day Britain declared war on Germany.

|

|

5. RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE WAR

In reviewing the events of 1914 it is natural to ask which country or which individual was primarily responsible for the outbreak of the war. The facts show that no simple answer to that question is possible. If we go back behind the immediate events, it is clear that the nations were subject to pressures and movements from which they could not escape. Nationalist desires, particularly in the Balkans, provided an explosive condition which, in the absence of any permanent machinery for peace, was waiting only for some spark to start a blaze. Alongside this was the growth of the rival alliances of the European Powers. The theory which many people cherished was that, because the rivals were so evenly matched in naval and military and economic resources, neither would venture to provoke a conflict. Events plainly belied this theory. Since all the great Powers were in one group or the other, the real danger was that a dispute that concerned any one of them would involve all of them. This possibility was rendered almost a certainty because a member of each alliance - Russia and Austria - had conflicting interests in the Balkans. It was as though two explosive agents met at one point to make a general explosion inevitable. Another common view was that international crisis after crisis had been dealt with peaceably and that in the twentieth century war was becoming out-of-date and no longer worth while. This easy optimism overlooked one important fact. The recent crises had been settled because each time someone had given way, and the impression grew that, in the last resort, someone always would give way. But here again events did not follow the expected pattern. Every time a nation yields to pressure it becomes not more likely t o yield next time but less likely, because it becomes more and more afraid that its prestige in the world will suffer or its interests will be sacrificed. So, in the end, some nation reaches the stickingpoint beyond which it will not go. This sets up resistances elsewhere, and war is the final result. That was what happened with Austria and Russia over their interests in the Balkans. We shall see this process still more clearly in 1939 when Hitler forced concession after concession until France and Britain would grant no more. When the responsibility of individual States is considered, the issue is far from clear. Same responsibility must rest on the Serbian Government which was aware of a plot against the Archduke but took no effective measures to prevent its operation. Nonetheless the primary responsibility must rest upon Austria. Her approach to the problem was deliberately provocative and was so framed as to make war almost inevitable. Her actions showed that she intended her ultimatum to be rejected. Germany's queries and objections to Austria's pressure were ignored. Relying upon the fact that Germany could do no other than support her, Austria dragged her ally into war heedless of the inevitable consequence that this must involve all Europe. Germany's immediate responsibility lay in the Kaiser's rash undertaking to support Austria without first ascertaining what Austria intended to do: last-minute advice and protests after the machine had begun to move were useless. All this must not be taken to imply that the Entente Powers were altogether blameless. The Russian Government was the first to order mobilization. This may have been a natural step in view of Austria's threats against Serbia and of the slowness of the Russian military machine. Moreover, mobilization was not in itself an act of war. But Russian mobilization encouraged similar moves by other Powers and so made a clash more likely. It was hardly to be expected that Germany would give to Russia all the time she needed to complete mobilization without Germany's making any preparations herself. The measure of France's responsibility is particularly difficult to assess. Though she did nothing to inflame the situation, she did little to ease it either by trying to restrain her ally Russia or by protesting to, or warning, her enemies Germany and Austria. The element of blame that often has been brought against Britain is that she did not make clear to Germany, until too late, that Britain would intervene on the side of France and Russia unless Austria was restrained. Right up to the outbreak of war most German politicians did not believe that Britain would involve herself in a Continental war. It is argued that if Germany had known with certainty that she would be confronted by the British Navy and by the manpower of the British Empire she would have compelled Austria to moderate her attitude towards Serbia. Whatever substance there may be in this view, it is not capable of proof. The truth seems to be that even responsible men in Britain were not clear whether Britain was bound to support France in the event of war. As we have seen, in the end these doubts were resolved by Germany's invasion of Belgium, after which there never was any doubt about Britain's attitude.

|

|

|

| |