|

The War at Sea

|

|

The real crux lies in whether we blockade the enemy to his knees, or whether he does the same to us. Admiral of the Fleet David Beatty, 1917

Although there were naval actions all over the world during the war, there was only one significant sea-battle during the First World War – the Battle of Jutland in May 1916; more than 250 ships on both sides were involved. But some historians believe that the war was won and lost at sea, because neither Britain nor Germany could grow enough food to feed their people. The side that ruled the sea would win the war.

|

Going Deeper

The following links will help you widen your knowledge:

Good account from

BBC Bitesize

U-boat warfare and the US

Sources on the Battle of Jutland

Voices of

WWI: August 1914 (plus transcript) - IWM Voices of

WWI: August 1914 (plus transcript) - IWM

YouTube

Really

clear, simple account from whawkvideo

|

Early Battles

The

key battles of the war were fought in the North Sea, where the British Navy

immediately established a blockade of German ports. Both sides were

terrified of losing:

- Heligoland Bight, Aug 1914

- On 28 August 1914, a British flotilla of 33 vessels ambushed a German naval patrol, sinking three ships and a torpedo boat, and damaging six other vessels in a confused battle at Heligoland Bight. The result was greater than the battle – the Kaiser ordered that the fleet should, "hold itself back and avoid actions which can lead to greater losses" … from then, on, the German fleet was ‘muzzled’.

- Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, Dec 1914

- Realising that it could not defeat the larger British Navy, the German High Seas Fleet tried to lure British ships into ambushes. In December 1914, a larger force of 17 vessels attacked the north-east:

- • half the ships attacked Hartlepool harbour, firing 1,150 shells and striking targets including the steelworks, gasworks, and railways;

- • the other half attacked the seaside resorts of Scarborough (damaging the Castle and the Grand Hotel) and Whitby (destroying the west front of Whitby Abbey).

- The tactic failed; the British ships nearby were too scared to intervene, and the German fleet turned and fled for home as soon as a larger British force approached. 122 British civilians were killed and 443 wounded, causing considerable outrage; ‘Remember Scarborough’ became an propaganda slogan encouraging men to enlist.

- Dogger Bank, Jan 1915

- In January 1915 the British – who were able to decode German wireless messages – learned of another raid, and were able to ambush the Group at the battle of Dogger Bank. The German ship

Blücher was sunk and the Seydlitz badly damaged ... and the Kaiser again ordered that German battle ships were not to be risked. The British, however had two ships badly damaged, making them also wary of a naval battle. The Germans realised that the British had known about the raid, but failed to realise that their wireless codes and been broken.

- Yarmouth and Lowestoft, Apr 1916

- In April 1916, a German force of eleven ships, supported by submarines and Zeppelin bombers, attacked the ports of Lowestoft (where the British kept their minelayers) and Great Yarmouth (a British submarine base). Again, British ships were not lured into battle, and again the High Seas Fleet fled as soon as the British fleet approached.

|

The German attack on Scarborough was a

propaganda defeat.

|

The U-boat campaign against Britain

The Germans used a new invention – the U-boat (‘undersea

boat’) – to sink ships bringing food and supplies to Britain.

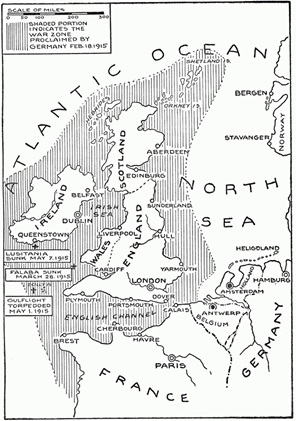

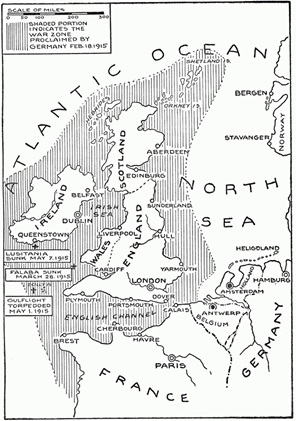

At first, they attacked the Royal Navy; by the end of 1914, German U-boats had sunk British 9 warships. However, British warships started travelling in a zigzag at speed, and the U-boats were unable to catch them to attack. The Germans also used submarines to lay mines in British coastal waters. In February 1915, as a retaliation to the British naval blockade, the German Admiralty announced a war zone around Britain, within which the Germans said they would sink ANY ship sailing to Britain

('unrestricted submarine warfare'). Up to February 1915, the Germans had only sunk 10 British ships. By August 1915 they were sinking two ships a day.

Britain depended on merchant trade for food, but also for raw materials

for war production.

|

Did You Know

The first submarine flotilla in history took place in

August 1914 when 10 U-boats set off from Heligoland. One broke down

and had to return to base; another was rammed and sank; another sank of its

own accord.. Just one torpedo was fired; it missed.

The "War Zone" announced by Germany on 4 February 1915.

|

|

The suspension of unrestricted submarine warfare

The danger with unrestricted submarine warfare was that

neutral ships were sunk, and neutral citizens killed.

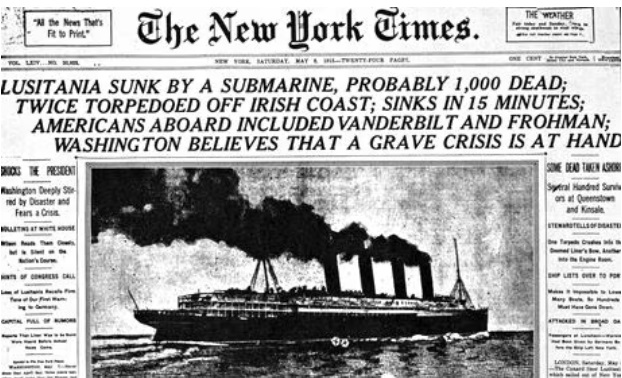

The American public was outraged when a U-boat sank the

Harpalyce, a ship taking food to starving Belgians (and clearly

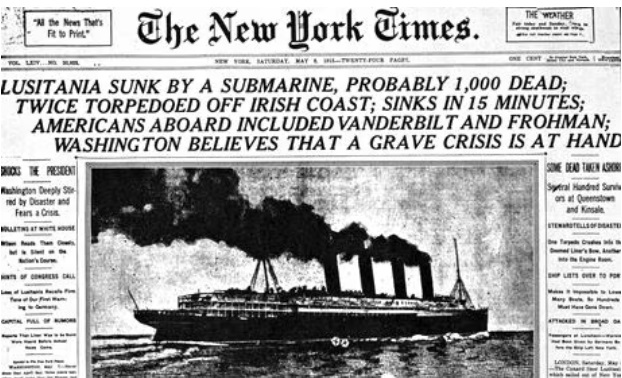

marked as such). There was even greater outrage in May 1915, when the Lusitania,

a passenger ship sailing from America to Britain was sunk with the loss

of 1,200 men, women and children. President Wilson warned Germany in three separate notes, the last of which (21 July) stated that sinkings of US ships would be regarded as ‘deliberately unfriendly’. When U-24 sank the liner SS Arabic,

outward bound for America, in August 1915, killing 3 American

passengers, therefore, the Germans stopped unrestricted attacks. -

After the sinking of the Sussex, an unarmed

French boat, in March 1916, Wilson threatened to cut diplomatic

relations with Germany ... as a result which the Germans agreed the

'Sussex Pledge' - not to attack passenger ships, and to allow crews of

merchant ships to abandon ship before sinking it.

|

May 1915, the Lusitania is sunk.

Unknown to the passengers, the Lusitania was secretly carrying bullets

and shells to Britain, which was why the ship blew up and sank so

quickly.

The sinking was a disaster for the Germans. The British government put out propaganda saying that the Germans were cruel killers of civilians.

More importantly, 128 Americans were among the dead.

|

Anti-submarine measures

The British tried different ways to stop the U-boats.

Q-ships: U-boats did not carry many torpedoes, so – when they found a ship on its own – U-boat captains came to the surface and sank it with their deck guns. To stop this, the British government started to put guns on merchant ships. From June 1915 they deployed Q-ships – which looked like a merchant ship, but were really well-armed warships. When the U-boat surfaced to attack what it thought was a merchant ship, the Q-ship would attack it. Depth charges: The British introduced the first effective depth charge, the Type D, in January 1916. But because hydrophones (to listen for the sound of U-boats) had not been fully developed by the end of the war, British battleships found it hard to find any U-boats to attack. Mines and submarine nets in the English Channel.

However, these measures proved ineffective, and by the end of 1916, the British had only sunk 15 U-boats. Yet by the end of 1916 German U-boats were sinking 1 in 4 merchant ships sailing to Britain. At one point, in 1917, Britain only had only two month’s supply of flour.

|

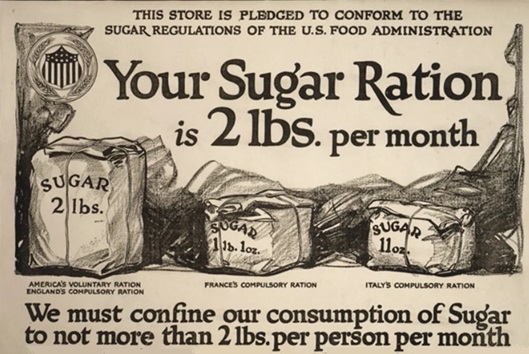

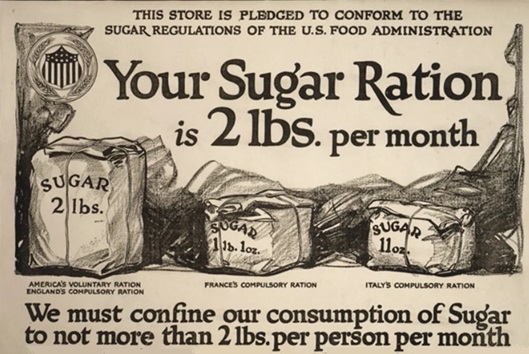

Rationing was introduced in Britain after December

1917, and ration books for butter, margarine, lard, meat, and sugar

issued in July 1918.

Was Britain really ‘in danger of losing the war’? Studies have shown that average energy intake decreased very little during the war.

|

|

The resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare

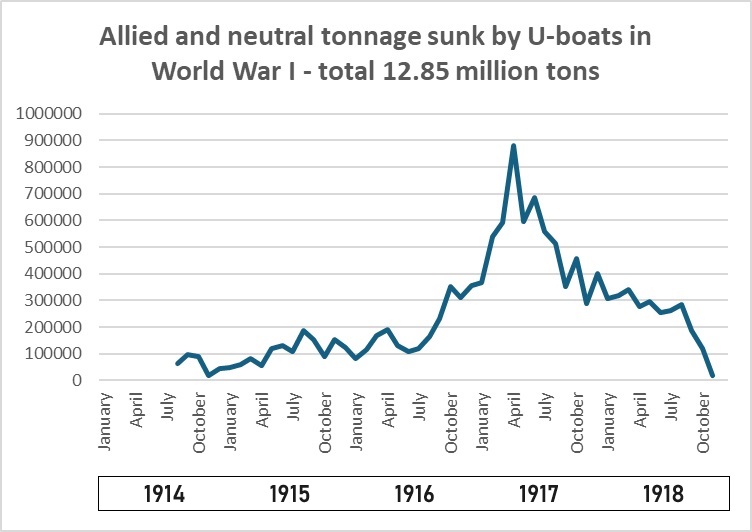

In 1917, after a furious debate, the German Admiralty again took the risk of unrestricted submarine warfare.

The key was a study which predicted that, if the U-boats could sink 600,000 tons

of shipping a month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace within six months.

On 31 January 1917, therefore – after Admiral Holtzendorff promised: “not one American will land on the Continent" – the Kaiser signed the order. And Holtzendorff was correct: US President Woodrow Wilson broke off diplomatic relations in February 1917, but he did not declare war.

Many Americans were isolationist and Wilson had won the 1916 election with the

slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” – it took the Zimmermann telegram to make America

declare war on Germany on 6 April 1917.

|

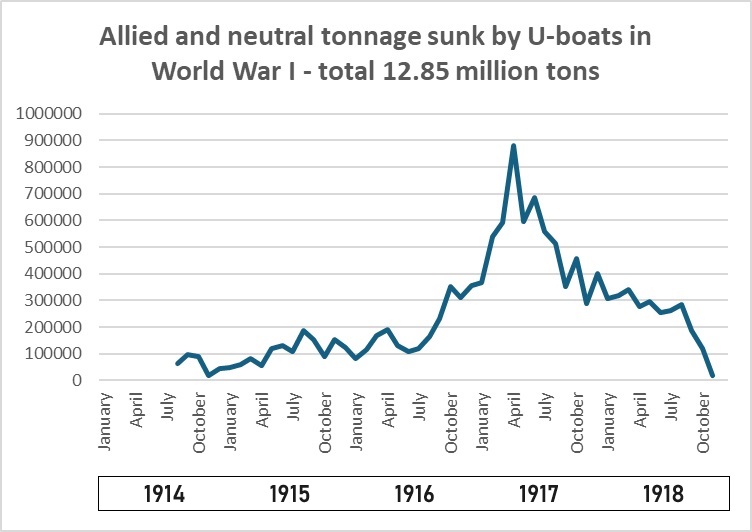

Source A

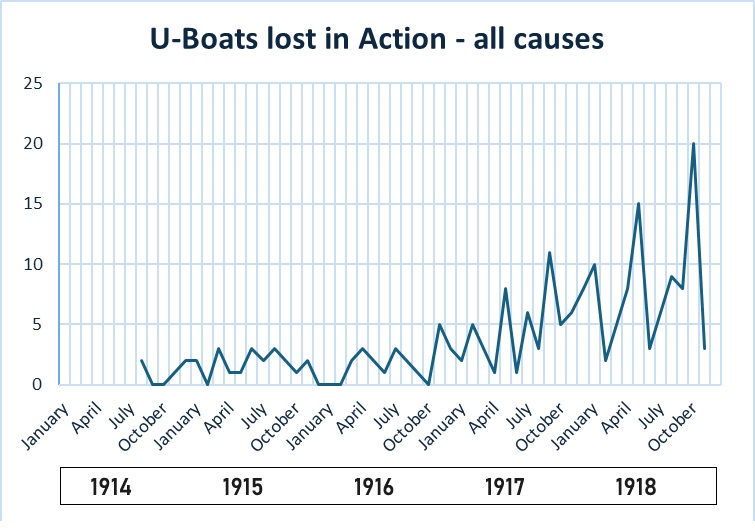

Shipping losses from U-boat action, 1914-18.

|

Anti-submarine measures (continued)

The uptick in shipping losses forced the British to develop

further ways of protecting shipping.

Convoys: After April 1917, the

British started to use convoys; merchant ships sailed in groups of 20 or

more ships, protected by battleships with depth charges.

This made it much harder for the U-boats to attack, even using torpedoes. As soon as they attacked one ship, the battleships knew where they were and could fight back with depth charges.

By 1918, the U-boats were only sinking 1 in 25 merchant ships sailing to

Britain.

American help: After the USA entered the war in April 1917,

also, American battleships protected the convoys as well as British battleships.

In August 1917, German U-boats sank 211 merchant ships but a year later

shipping losses had been halved, and fell rapidly thereafter.

Also, America started sending American wheat to Britain

(before, the only wheat going to Britain was from Australia, on the other side

of the world).

|

Shipping losses from U-boat action, 1914-18.

This graph is compiled from this webpage;

if you look at the list, you will see which were the most effective

ways of countering the U-boats. You will also see that U-boat

technology was still in its infancy.

|

|

While the German U-boats were trying to sink British merchant

shipping and starve Britain to death, the British navy was blockading German

ports to try to starve the Germans to death.

In 1916, the German navy came out to try to break the blockade. The British Grand Fleet was commanded by Admiral Jellicoe and the Germany Hugh Seas Fleet by Admiral Scheer. On 31 May 1916 they opened fire on each other. The two fleets were 15 km apart. The German gunners were better than the British gunners. Also, the German shells went easily through the British ships'

armour and blew up their ammunition stores; three British ships just blew up. Admiral of the Fleet David Beatty commented: “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.” British losses were much greater. The British lost 14 ships – 3 of them battleships – and 6,000 men killed.

The Germans lost 11 smaller ships (only one big battleship) and just

2,550 men. Although he was winning the battle, Admiral Scheer was worried. The British fleet was much bigger than the German fleet. Scheer knew that if he lost this battle, German would lose the war.

He turned away and went back to port. Jellicoe also knew that if he lost this battle, Britain would lose the war. He did not try to stop Scheer getting away. -

The naval historian Andrew Gordon has argued

(controversially) that Jutland was not a 'battle' at all, and should really be

regarded as a series of skirmishes.

|

Consider:

1. Make a list of the key dates in the battle with the

U-boats.

a. Click on the graph of shipping lost (Source

A) to bring up a larger version; can you link the shape of the graph

to the developments in the battle with the U-boats?

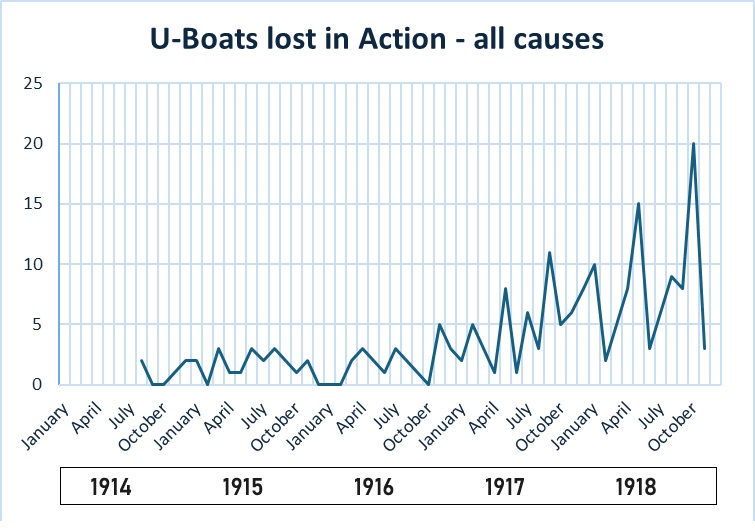

b. Now repeat, comparing the graph of U-boats

lost (Source B) to the key developments in the U-boat war - which

developments seem to have had little effect, and which were more

successful?

2. Make a table of U-boat 'successes' and

'failures', and use it to write an essay: "How successful was the

German U-boat campaign?"

3. What points would you make if you were

asked to argue that the War at Sea was the Allies'

'war-winning-weapon'? What points would you make if you were asked

to argue against that view?

- AQA-style Questions

3.

Write an account of how the British won the war at sea.

4. ‘The war at sea was the main reason for Germany’s defeat in the First World War.’ How far do you agree with this statement?

-

iGCSE-style Questions

(a) Describe TWO features of the sinking of the Lusitania.

• Describe TWO features of the U-boat threat to Britain.

(b-c) Click to see the questions

|

When is a defeat not a defeat?

The Germans claimed victory, but they never left port again

(and, when ordered to do so in November 1918, the sailors mutinied).

So, although the Germans gave the British navy a bloody nose, the blockade continued. The German people got more and more hungry. The German Board of Public Health claimed that three-quarters of a million Germans died from hunger and disease associated with the Blockade, and scurvy, tuberculosis and dysentery were widespread. In 1918, Germans were living on

K-Brot,

potatoes and berries; there were Hunger Riots in Germany in autumn 1915, summer

1916, and September 1918; and – fearing a Communist revolution – the German

government was forced to end the war.

In this way, Jellicoe’s ‘defeat’ at Jutland can be classified as a ‘war-winning weapon’!

|

|

|

Spotted an error on this page? Broken link? Anything missing?

Let me know.

|

|