|

|

NOTE: this is not a topic on any of the GCSE specifications, but it will help you understand the war, particularly your appreciation of the different interpretations.

|

|

|

THE ORTHODOX INTERPRETATIONThe first history of the war was written whilst it was still happening, in 1964. Journalist David Halberstam’s Making of a Quagmire created an image and an interpretation which has become known as the orthodox interpretation of the war: that the United States, driven by well-meaning anti-communism but lacking understanding of Vietnamese nationalism and culture, was drawn into a guerrilla war it could not win, in support of a weak South Vietnamese government and its useless army. In the 1980s, journalists Stanley Karnow (1983) and Neil Sheehan (1988) cemented this interpretation with best-sellers. “All three of these journalists,” comments the revisionist historian Mark Moyar waspishly, “were entertaining writers, and awful historians” … and their analysis became the accepted interpretation. This is still the predominant interpretation of the war, though it has been developed and refined over time as more information has become available. Ideas which have been added include: 1. Flawed containment:

2. The lure of technowar:

3. The First Domino:

4.

A counterfeit creation:

5. Faulty lessons from history:

6.

Ambition, arrogance and optimism:

7.

The War of Ideas:

8. The Last Domino:

… but the basic orthodox interpretation has remained: that the US had simply taken on too much, and that America’s leaders had taken that US into a war which was endless and unwinnable. In 1999 American History Professor Fredrik Logevall stated that it was “axiomatic” (= undeniable/ beyond contradiction) that the United States had erred in deciding to intervene in Vietnam. He could not have been more wrong! The orthodox interpretation may indeed be true, but it is most certainly not above contradiction.

|

A cartoon by Bill Mauldin.

|

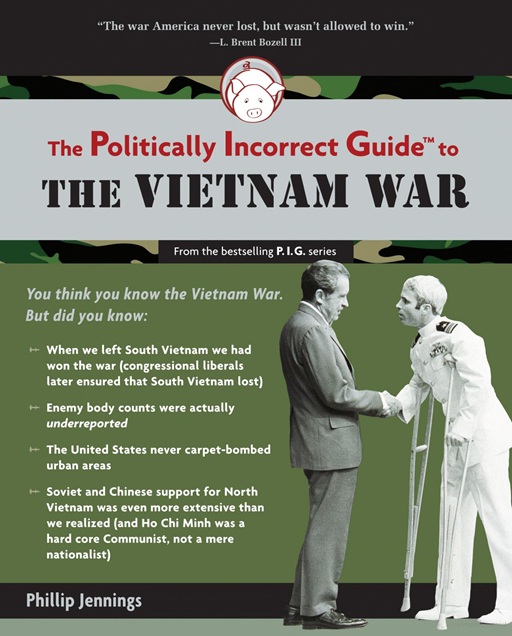

REVISIONIST INTERPRETATIONSThe publication of the Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg in 1972 showed, not a well-meaning government that had blundered unwarily into war, but which had cynically and knowingly lied to the public. This unleashed a whole load of revisionist theories: 1. Stalemate: In The Irony of Vietnam (1978), Gelb and Betts advanced the ‘stalemate’ theory that – bound by the Washington bureaucratic ‘system’, by domestic politics, and by fear of widening war – America’s leaders, even as they escalated the conflict, were simply doing “the minimum necessary” to avoid defeat .. they were not trying to win. 2. A Strategy for Defeat: in the 1980s, a raft of former US generals and advisers – and, powerfully, the historian Gabriel Kolko (1985) – went into publication accusing the government of forcing the Army to fight “with one hand tied behind their back” – for instance stopping them bombing North Vietnamese cities, and in particular limiting the fighting to a ‘war of insurgency’ in South Vietnam: not accepting that the War was all-along really a war against North Vietnam. 3. The ‘stab-in-the-back’: along with their accusations of a conscious strategy for defeat, revisionists then blamed pusillanimous politician and anti-war campaigners of siding with the enemy against the military and losing the war on purpose. (If you are also studying Germany or the Treaty of Versailles, you will realise that this is a common complaint of an army which has lost a war without being defeated.) In 2008 the revisionist Mark Moyar (of the US Marine Corps University) accused Halberstam, Karnow and Sheehan, who were all journalists in Vietnam during the war, of actually causing America’s defeat in some dreadful self-fulfilling prophecy – that their treasonous and hostile reports and influence were the reason that the US ditched Diem and Americanised the war in 1963-64. 4. Hearts and Minds: revisionist historians argued that US strategy devoted too much attention to warfare, to the detriment of ‘pacification’ (which had actually proved quite successful in 1968-73). Instead, however, Rolling Thunder and search-and-destroy fuelled hatred and nationalism and “in an attempt to solve a problem that did not exist, [the US] created a problem that could not be solved” (Cable, 1988). 5. A Necessary War: putting the Vietnam War into its global context of the Cold War, revisionist historians such as Michael Lind (1999) argued that the US had NOT misjudged US interests. There really was a Communist plot to take over south-east Asia, and South Vietnam “thus acquired an international significance out of all proportion to its size (RB Smith, 1983). Ho Chi Minh had visited China in 1962 to get support for the war (just as Kim Il Sung had visited Moscow and Beijing in 1949) and Chinese support for North Korea was huge. In 1978 Guenter Lewy (who had special access to classified documents) argued that President Johnson simply saying that Vietnam was vital to US security interests made it so in front of a watching world. 6. A Noble War: in the same book, Lewy advocated that the US was morally right to go into the Vietnam War – which President Ronald Reagan later called “a noble cause”. Orthodox historians, the revisionists asserted, had been duped into thinking that the NLF was about patriotism not communism. Did they not realise that North Vietnamese communism was particularly nasty and repressive, and that the NVA/VC regularly committed atrocities of their own? Not only that but, Lewy argued, “the sense of guilt created by the Vietnam War in the minds of many Americans is not warranted and the charges of officially condoned illegal and grossly immoral conduct are without substance”; ie we should ignore Agent Orange and My Lai – the US had genuinely tried to minimise the ravages of war. 7. The First Lost Victory: Diem has had a major makeover in recent years – he was NOT the cardboard cut-out ‘little dictator’ caricature that orthodox historians had made him out to be. Historians have admired his suppression of the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao ‘sects’ (which were not sects at all, but paramilitary organisations) and the Binh Xuyen (which were the Vietnamese equivalent of the Mafia), seeing it as a key step in getting a ‘wild west’ country under control. Meanwhile, Mark Moyar (2008) claimed that the local ‘informants’ used by journalists Halberstam, Karnow and Sheehan for their negative reports about Diem’s government were in fact Communist agents, and that the Buddhist protesters of 1963 had been by infiltrated by NLF Communists and fabricated most of their ‘oppression’. Diem, the revisionists assert, was in fact a Vietnamese patriot, and a viable alternative to NFL Communist patriotism, and was winning by 1963 … just as the US decided to get rid of him. 8. The Second Lost Victory: along with Diem, the ARVN have also received a posthumous upgrade. Historians have found that – because it was seen as a route for self-advancement -- ARVN soldiers were generally better-qualified, and of higher social-class, than the US draftees. They also point out that – although admittedly supported by Operation Linebacker – all but a few US troops had left South Vietnam by 1972 = it was the ARVN who defeated the Easter Offensive = not so useless after all. As a corollary to their ‘stab-in-the-back’ accusations, revisionists such as Phillip Jennings (2010) have asserted that the ARVN had actually WON the war by 1973, and that ‘congressional liberals’ gave away the victory by refusing to support South Vietnam in 1975.

|

The cover of Phillip Jennings's book (2010).

|

RECENT INTERPRETATIONSThe debate between orthodox and revisionist historians is bitter. Orthodox historians accuse the revisionists of ‘what-if’ conjectural history. The revisionists accused the orthodox historians of naivety and political correctness. An attempt at a synthesis by John Dumbrell (2013) – approving some claims and dismissing others from both sides – simply earned him criticism from both sides. The latest histories, however, have been able to take a new line because of the opening of archives in Russia and China, which has allowed historians to see the war in a wider context than just “American scholars asking American-oriented questions and seeking answers in documents produced by Americans”. Above all, historians are beginning to study how the Vietnamese themselves saw the period, pulling out anthropologists’ studies of Vietnamese society, interviews with Vietnamese refugees, and writings by Vietnamese historians … in what Cambridge University’s Andrew Preston has called ‘the Vietnamese turn’. They are giving the Vietnamese – as Miller and Vu termed it in 2009 – ‘agency’ in their own war, and getting some very different interpretations of what was going on. One recent book is entitled: The Long Resistance, 1858-1975. Another takes the dates 1930-75. Vietnamese-American scholar Nu-Anh Tran has interpreted the period 1945-75 in terms of "contested nationalism" (ie as a civil war between North and South Vietnam, both offering their own, equally authentic, different kind of nationalism). Other historians have revised their view of the Diem regime, and of DRV strategies and internal divisions, and the NVA during the War. Pierre Asselin (2002) showed how the North Vietnamese were not just tools of China and Russia, and made independent decisions. Above all, historians are seeing that the war was not just a political/military event, but social, economic & cultural and are, eg, studying the contribution (and abuse) of women to the war. They have found that the exodus of Catholic refugees in 1954 was not a mindless panic caused by US propaganda, but based on known experience of the Viet Minh. Local situations – such as the race-war between Vietnamese and Khmers in the Mekong Delta – can be seen to have affected the bigger picture: “The lines of battle were not just between ‘Viet Cong’ and the People’s Army of Vietnam units on the one hand and ARVN and American forces on the other; nor can the conflict be reduced to nothing more than a clash between the Soviet Bloc and the United States-led ‘Free World’. Different Vietnamese social groups played different roles in the war.” Miller and Vu (2009). “The sad truth is, Vietnam never mattered to the United States”, reflected Andrew Preston (2013).

|

|

Consider:When an author writes a book, they choose a title which, for

them, sums up what they are trying to convey. Below are the titles of some

of the books that have been written about the Vietnam War. For each,

consider what impression/interpretation of the War it conveys. What would YOU choose as the title of YOUR book on the War?

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spotted an error on this page? Broken link? Anything missing? Let me know. |

|