An extract from S Reed Brett, European History 1900-1960 (1967)

S Reed Brett was a textbook writer from the 1930s to the 1960s.

You may find this hard and boring, but it was the kind of textbook we were using with students your age when I started teaching!

NATIONALIST AGGRESSIONS

Conscription

Restored, March 1935, Rhineland Re-occupied, March 1936, Annexation of Austria, March 1938, Sudetenland Crisis, 1938, Czechoslovakia Dismembered, Results

of Czechoslovakia’s Disruption.

The

Russian dilemma, Germany and

Poland, Moscow

Non-Aggression Pact, 23rd August 1939.

|

4. GERMANY'S FOREIGN POLICIES

|

GERMANY'S FOREIGN POLICIES

| |

Conscription Restored, March 1935

Most of the aggressions, leading step by step to open war in September 1939, were the outcome of the deliberate policy of Hitler… By 1933 and 1934 he had established his supremacy in Germany. Thenceforward he aimed to wipe out the stigma placed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, to recover territories that that Treaty had taken away, and to re-establish Germany as one of the great Powers of Europe.

The first step towards these ends was taken on 16th March 1935 when the German Government issued a decree restoring universal military service. The decree was accompanied by a statement that when, under compulsion, Germany had submitted to disarmament, the Allies had declared this to be part of a policy of general disarmament, yet this general policy had never been carried out. (Indeed, on the day previous to Germany’s decree, France had increased the length of service in her own Army.) Germany therefore refused any longer to remain disarmed while surrounded by neighbours whose own armaments were increasing. Whatever may be thought of this justification for German rearmament, the action unquestionably was a breach of the Treaty of Versailles. Moreover, by its very nature, more breaches were likely to follow: clearly Germany’s purpose was to use military force in order to assert herself as a power in Europe, and sooner or later this would involve a clash with some other nation that thought its security threatened.

|

Conscription Restored, March 1935

|

Rhineland Re-occupied, March 1936

Europe had to wait less than twelve months for the first evidence of the use to which Hitler intended to put his new army. On 7th March 1936 he sent it to re-occupy the Rhineland, up to the French frontier, which the Treaty of Versailles had demilitarized. It was a risky undertaking, and Hitler’s own generals had advised strongly against it. The German Army, new and small, could have been routed by the French alone; and a combination of neighbouring armies could have overwhelmed Germany and reduced her to a new powerlessness. It was one of Hitler’s early gambles, and his guess proved to be correct. None of the former Allies felt certain that in a crisis the others would give support, and none was willing to act alone. So Hitler not only achieved his immediate objective but he was encouraged to use similar methods elsewhere in the future.

One of the most serious aspects of the re-occupation of the Rhineland was that it was a breach of the Locarno Agreements of 1925. Hitler might claim that Germany was no longer bound by the Versailles Treaty because it had been imposed by force, but she could offer no such reason for ignoring the Locarno Pact to which she had agreed freely on equal terms with her fellow signatories France, Britain, Italy, and Belgium. Indeed the originator of the Pact had been Germany’s Foreign Minister Stresemann. If, to suit his convenience, Hitler could thus violate a promise freely given, the nations could have little confidence in any future assurances that he might give. Without such confidence in the good faith of nations, there could be no secure peace.

As time passed, and as Hitler became stronger, he grew bolder in aggression. In April 1938 Germany annexed Austria; in September 1938 she claimed the Sudeten areas of Czechoslovakia which in consequence was dismembered and destroyed; and in March 1939 Hitler began his attack on Poland, and it was in order to make good their assurances to Poland that Britain and France finally went to war in September 1939.

|

Rhineland Re-occupied, March 1936

|

Annexation of Austria, March 1938

Union between Germany and Austria was not a new idea. The union (Anschluss) movement went back to the days immediately following the First World War, and the initiative towards it had then come not from Germany but from Austria. Early in 1919 the Austrian Assembly declared that Austria was a democratic republic and proclaimed the union of Austria with the German Republic. There were strong arguments, economic and national, in favour of such a union; but neighbouring Powers, particularly France and Czechoslovakia, fearing that the combined State would become dangerously powerful, vigorously opposed the union. Consequently the Treaty of St Germain, of September 1919, forbade any modification of Austrian independence. In spite of this, there always had been people in both Germany and Austria in favour of the Anschluss,

Hitler’s attack on Austrian independence, of which some account was given above, had other motives. His was a policy of German aggrandizement which was helped by the growth of an Austrian Nazi Party. In 1934 an attempt of the Nazis to seize power resulted in the death of Chancellor Dollfuss but failed in its main objective. This was due mainly to Mussolini’s support of Austria. But the formation of the Rome-Berlin Axis in 1936 altered the whole balance of political power in central Europe. Thereafter it could be only a question of time before Hitler renewed his attack on Austria.

By 1938 he felt himself strong enough to act, and it was difficult to see who was likely to stop him. The League of Nations, though nominally still in existence, was in practice defunct: the United States still abstained from it; Japan had withdrawn from membership in March 1933, Germany in October 1933, and Italy in 1937. In the earlier threats to peace, the League had done nothing effective. France, the only Continental nation that might be disposed to challenge Germany, would be barred geographically by Germany and Italy from contact with Austria. Moreover, Austria would not be of one mind in opposing union with Germany: the Austrian Nazi Party had a good deal of support and was the counterpart of the old Anschluss movement. Thus Hitler could feel confident that the time was ripe to use his new army to overrun Austria.

In February 1938 the Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg received an invitation to visit Hitler at the latter’s residence at Berchtesgaden in Bavaria. Schuschnigg, imagining this to be a normal meeting for friendly consultation, found himself browbeaten by Hitler who, after a long harangue, delivered an ultimatum: a Nazi named Seyss-Inquart was to be appointed Austrian Minister for Public Security (that is, in charge of the police); all imprisoned Nazis were to be released; and a hundred German officers were to be accepted for service in the Austrian Army. After some resistance Schuschnigg was forced to sign his acceptance and he was given three days during which to carry out the terms of the ultimatum. He then was allowed to return to Vienna. There he tried to escape from the net, but no help was forthcoming either from within Austria or from outside.

On 9th March Schuschnigg announced the holding of a plebiscite on the question of Austrian independence. This was angrily forbidden by Hitler. On 11th March Seyss-Inquart was appointed Austrian Chancellor in place of Schuschnigg. By that time German soldiers already were crossing the frontier, and on 12th March Vienna was a German-occupied city. Two days later Hitler arrived in the city, greeted with all the usual paraphernalia of Nazidom: masses of saluting people, swastikas hung or flown from every possible point (including the cathedral spire), and peals of church bells.

Austria as a separate State no longer existed: it became the ‘Ostmark’ of Germany, and Seyss-Inquart was Hitler’s ‘Regent’. The Austrian national bank was absorbed by the Reichsbank, and the Austrian Army by the Reichswehr. German troops plundered shops and other premises almost at will. There were wholesale arrests of non-Nazi Austrians, and Jews in particular were subject to terrible privations and persecution and deportation to concentration camps. Clearly Hitler, who was capable of perpetrating such violence, would be capable of any action that suited his convenience or ambition. Events showed that each success enlarged his violent ideas and inflamed his passion for further power.

|

Annexation of Austria, March 1938

|

Sudetenland Crisis, 1938

His next victim was Czechoslovakia. In the previous chapter some explanation was given of the minority problem of Germans living in Sudetenland and of the effect that Germany’s seizure of Austria would have upon Czechoslovakia: she would be vulnerable to any foreign attack because her important western half would be surrounded by German-controlled territory.

The Sudetenland was the ridge of mountain territory on the borders of Bohemia and Moravia in which lived 3 million German-speaking people formerly subjects of Austria. The Czechoslovakian Government had been wise enough to treat this minority group liberally: it had full parliamentary representation and equal political facilities. On the other hand most of the public officials were Czechs, and this was liable to produce local friction. Nevertheless it is true that the Sudeten Germans were treated much more generously than minorities usually were, and there need never have been serious trouble if it had not been stirred up from the outside.

The first open sign of political movement among the Sudetens was the formation of the Sudeten-German Party in 1935 under the leadership of Konrad Henlein. At first this was not allied to the German Nazi Party, but in so far as it emphasized the rights of Germans, there was much common ground between the followers of Hitler and of Henlein. Here was fertile soil to work when the proper season should arrive.

For the success of German intervention, much would depend upon the attitude of other Powers. France held one of the keys to the situation. It had been with French encouragement that the Little Entente had been formed, and during the years 1924-27 France made alliances with each of the three members Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Rumania. Consequently, if Hitler intended to interfere in Czechoslovakia he would need to calculate the chances of French intervention. As the years passed after 1935 the Sudetenland movement grew stronger in its pro-German ideas until in April 1938 Henlein boldly demanded self-government for the Sudetenland areas. This was Hitler’s moment. It was also a moment when France was powerless to take effective action. In that same month a new ministry came into office in France, following another which had lasted only four weeks. The new Premier, Daladier, was a man of some ability and vigour (and was to achieve the somewhat remarkable feat of remaining in office for two years, that is, until March 1940), but his Foreign Minister, Bonnet, was a peace-at-any-price man. Bonnet was content to hitch his policy to that of the British Premier, Neville Chamberlain, whose policy of ‘appeasement’ tallied closely with Bonnet’s. Because it became clear that France would not honour her treaty obligations, Czechoslovakia’s fellow-members in the Little Entente felt it unsafe to support her. Thus the events of 1938 make up a deplorable story in which France and Britain, yielding to one after another of Hitler’s demands, step by step gave away Czechoslovakia’s territories and rights until her defences were completely destroyed and she could be broken up at Hitler’s pleasure.

|

Sudetenland Crisis, 1938

|

Czechoslovakia Dismembered

During the middle months of 1938 the political atmosphere in Europe was working to a climax. It was a speech by Hitler on 12th September which kindled the Sudeten blaze. He declared: ‘Three and a half million Germans are being oppressed in the Czech State . . . If these tortured souls cannot obtain rights and help by themselves, they can obtain them from us.’ Riots in the Sudetenland caused the Czech Government to declare martial law, and Henlein fled to Germany.

So explosive was the situation that Neville Chamberlain, the British Premier, decided to try what personal negotiations with Hitler would effect. Three times within a fortnight Chamberlain flew to meet Hitler, each time making concessions in the hope that they would satisfy Hitler’s ambitions and so would avoid a general war.

On 15th September Chamberlain was at Hitler’s mountain residence at Berchtesgaden. There it was agreed that the ‘principle of self-determination’ should be applied. That meant that the inhabitants of the Sudetenland should be allowed to determine by their votes whether they would prefer to remain in Czechoslovakia or to be transferred to Germany. New boundaries were to be drawn according to the results of the voting. This plan was accepted by the British Government and by the French; and Britain and France were to guarantee the new boundaries.

In order to convey to the Fuhrer this acceptance, and to settle its details, Chamberlain flew to Godesburg on the Rhine on 22nd September. To his dismay he found that during the interval the situation had changed drastically in two respects. First, Hitler had abandoned all ideas of a plebiscite and was demanding that German soldiers should march at once into the German areas of the Sudetenland. It would seem that, imagining that the British and the French would reject the Berchtesgaden proposals, he had expected that he would have a pretext for the war that he was itching to wage. Second, Hungary and Poland also had put forward claims to areas of Czechoslovakia in which their languages were spoken, and these claims were supported by Hitler. Hitler fixed 1st October as the date on which the German occupation would take place. Chamberlain returned to London a defeated negotiator. France ordered the partial mobilization of her Army, and the British Admiralty ordered the mobilization of the Royal Navy.

On 28th September Mussolini intervened to ask Hitler to postpone the occupation of the Sudetenland for twenty-four hours beyond 1st October. The result was that on 29th September Chamberlain flew to Germany a third time. A four-Power Conference was held at Munich where Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, and Mussolini met to settle the question of war or peace. Perhaps the most notable fact about the Munich Conference was the absence from it of a Russian delegate. Russia had been ignored deliberately. Thus four statesmen conferred on the fate of Czechoslovakia and, on 30th September, they drew up the Munich Agreement. In essence it conceded all Hitler’s demands with the addition of certain face-saving clauses. The German-Czechoslovakian frontier was to be fixed not by Germans but by representatives of the four Powers and of Czechoslovakia; inhabitants of the border areas were to be allowed to move into another adjoining area if they so wished; Britain and France would guarantee the new boundaries; and Hitler moved his occupation date from 1st to 10th October.

Momentarily Europe breathed freely. Munich had saved the world from war. But the sense of relief was brief. France had defaulted from her treaty undertakings with Czechoslovakia. Britain had no such undertakings and therefore could not be accused of treachery. But these Powers together had submitted completely to Hitler’s blustering threats, and in the process had consented to watch one of the most truly democratic countries in Europe while it was crushed by a dictator. Recent history had shown that Hitler’s assurance that: ‘This is the last territorial claim I shall make in Europe’ was not likely to be kept any longer than his other promises had been. Winston Churchill’s speech in Parliament proved to be only too true: ‘Terrible words have for the time being been pronounced against the western democracies: Thou art weighed in the balances and found wanting.’

For Czechoslovakia the result of Munich was disastrous. In spite of British and French guarantees, the Germany Army was allowed to move into Sudetenland and to work its will. Slovakia became self-governing; the Poles sliced off a piece of Moravia; and the Hungarians took Ruthenia from Slovakia. In October Benesh resigned as President of Czechoslovakia and went into exile. In March 1939 the process of disintegration was completed: the German Army overran what was left of Czechoslovakia; they occupied Prague; and the great Skoda armament works henceforward would produce for Germany. While Slovakia became a separate and nominally self-governing State, what remained of Bohemia and Moravia became a Protectorate of the Reich.

|

Czechoslovakia Dismembered

|

Results of Czechoslovakia’s Disruption

The virtual annexation of Czechoslovakia was in line with others of Hitler’s aggressions in that it showed a complete disregard of his own pledged word. But in one important respect it was different: hitherto Hitler had claimed that his purpose was to give justice to Germans in the Rhineland and in Sudetenland. His treatment of Czechoslovakia, however, was the annexation of non-German territory and people. Inevitably the rest of Europe asked where this process would stop. Hitler’s use of the name ‘Third German Reich’ carried people’s minds back to the Reich which had been the Holy Roman Empire: this had stretched across the Alps into Italy and across the Rhine into France. It would seem that there was no limit to Hitler’s ambitions, that his real object was Lebensraum: living-space for Germans and therefore that no country would be safe from his aggressions, least of all countries like France and Britain that had colonial empires ideal for occupation by an expanding population.

On two grounds, therefore, Czechoslovakia’s disruption changed the attitude even of peace-loving Britain and France. First, Hitler’s flagrant breach of solemn promises at Munich was an insult to his fellow-signatories so that even Chamberlain swung from further ‘appeasement’. Second, fear for their own security drove Britain and France to feverish military preparations. In April 1939 Britain adopted a measure of military conscription: never before in her history had she done so in time of peace. Perhaps the best that can be said for the Munich agreement is that it allowed a little time during which preparations could begin for Hitler’s next threat to peace.

|

Results of Czechoslovakia’s Disruption

|

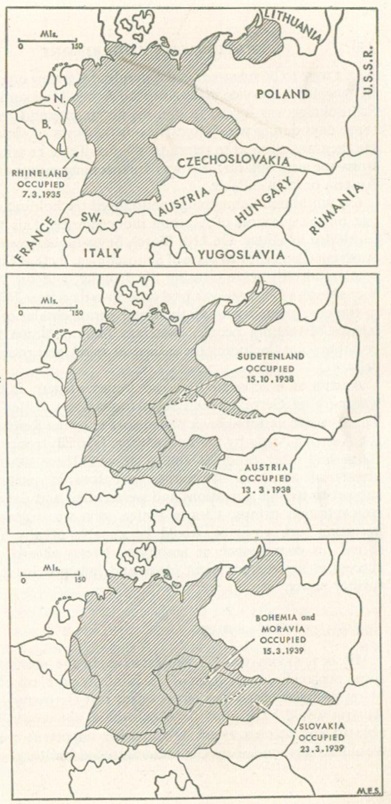

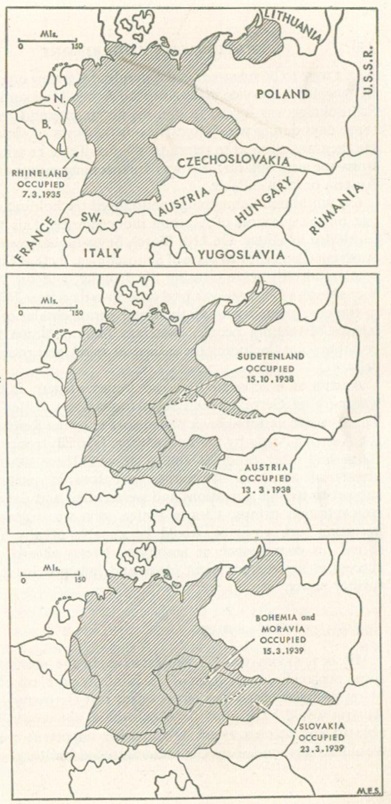

Expansion of Germany 1935-1939; |

|

5. RUSSIA AND POLAND

Germany’s last, and decisive, act of aggression was her invasion of Poland. To understand the nature of this event, we need to consider the situation not only in Poland itself but also of Poland in relation to Russia.

|

RUSSIA AND POLAND

|

The Russian Dilemma

One of the outstanding and unalterable characteristics of the Nazi creed was bitter hatred of Communism and therefore of Soviet Russia. The natural result should have been common action between Russia and the Western Powers to check Hitler as he went from aggression to aggression. This did not happen, and the responsibility for Russia’s isolation lay mostly with the West. Britain, and to a less degree France, disliked Communism only a little less than Hitler did, because Communist dictatorship was the opposite of Western democracy. Also, in spite of all that the Five-Year Plans had done to develop the economic and military resources of Russia, there was a widespread belief that she would not be able to sustain a large-scale war.

The Russians, on their part, mistrusted both the integrity and the effectiveness of the West, and with some reason. Russia, watching the feebleness and indecision of Britain and France in face of Hitler’s threats, could not but conclude that such nations would not be reliable allies for herself. More than this, the Russians believed that the four capitalist Powers, during their negotiations at Munich, from which Russia had been excluded, had agreed secretly upon a policy against Communist Russia. Alongside this, many Russians suspected that the Western Powers would be glad to see Germany and Russia exhausting themselves fighting each other while the Westerners preserved their resources ready to make war on the victor.

Nevertheless it was Nazi Germany that Russia chiefly feared. In any conflict between them, the all-important factor would be Poland which was a buffer-State separating one from the other. It was essential to Russian security that Germany should not be allowed to absorb or dismember Poland as she had done Czechoslovakia. If German troops were allowed to mass behind Poland’s eastern frontier they would be able to launch an attack on Russia with all the advantages of a planned offensive. Russia’s policy towards Poland was to reverse this policy: she insisted that any treaty must include a proviso that would give to her the right, immediately any act of German aggression took place, to send troops into Poland and the Baltic States as a defence against a German invasion of Russia. The Poles always refused to consider any such proposal because they were afraid that if the Russians were once established in Polish territory they would remain after the war ended.

Thus, while there was hatred between the Nazi-Fascist Axis and Communist Russia, there was no confidence between Russia and the Western democracies. Stalin therefore began to think of obtaining at least a temporary measure of security by making his own terms with Hitler.

|

The Russian Dilemma

|

Germany and Poland

In the meantime Hitler’s own experiences were leading to a similar conclusion. This also arose from his dealings with Poland. Under the Treaty of Versailles, Poland was given access to the sea by a ‘corridor’ of territory much of which had been German which reached the Baltic at Danzig, though Danzig was to be a free city under League administration. One of Hitler’s earliest aims when he attained power was to annex Danzig to Germany. Towards the end of 1934 Nazis in Danzig obtained control of the city and then ignored its constitution and the authority of the League. From time to time Hitler’s speeches included demands for the transfer of Danzig and for a strip of land across the Corridor so that road and rail communication could be built to link East Prussia to the rest of the Reich. After German successes against Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938, Hitler renewed these demands formally.

It was on this point that Britain and France at last took a stand. In March 1939 Britain gave to Poland a guarantee that if her independence was threatened, so that Poland felt compelled to use force to resist, the British would ‘lend to the Polish Government all the support in their power’. In one respect it was strange that Britain, having watched the dissolution of Austria and Czechoslovakia without moving a soldier to prevent it, should give such a pledge to Poland whose remoteness would make it impossible for Britain to help her if she were attacked. The fact was that Chamberlain had become disillusioned at last: Hitler’s repeated breaches of promises were felt to be deliberate humiliations of the Prime Minister himself and of Britain. The point had been reached at which even Chamberlain would yield no further.

On Hitler’s side there was one fatal obstacle to his occupation of Poland: he was confident that he could defeat the Poles; Britain was too remote to be effective in Poland’s defence; France would follow Britain; but what would Russia do? If Russia supported Poland the result might be in doubt, and Russian support of Poland would give time and encouragement to Germany’s enemies to attack from the west. There seemed only one answer: reluctantly Hitler decided that he must make temporary terms with Stalin as a preliminary to attacking Poland.

|

Germany and Poland

|

Moscow Non-Aggression Pact, 23rd August 1939

Thus Stalin and Hitler, each from his own standpoint and each in his own interests, had reached a common conclusion the need for a Russo-German Pact. Having reached it, they lost no time in carrying it into effect. After brief preliminary negotiations, on 23rd August Ribbentrop, the German Foreign Minister, flew to Moscow and that same day a Pact was signed.

By its terms the two countries undertook that neither would go to war against the other and they agreed on a line of demarcation between their respective spheres of influence in Poland. The Pact was to remain valid for ten years.

Much more important than the details of the clauses was the fact of the agreement itself. It was the complete reversal of what had been fundamental in the political creeds of the German Nazis and of the Russian Communists. It was the one event that the diplomatists of the world had known could never happen. It has been called truly ‘the greatest diplomatic bombshell of the century’ which ‘exploded over a stunned Europe’.

The immediate, practical effect of the Pact was to clear the way for an offensive against Poland. Once again, there would be no difficulty in finding or inventing reasons for hostilities. It was claimed that Germans in Poland were being brutally ill-treated, that Polish troops had fired across the frontier, and so forth. Without any formal declaration of war, on 1st September 1939 German troops and planes crossed the frontier into Poland. On 3rd September Britain, in accordance with her guarantee to Poland, declared war on Germany and France, somewhat hesitatingly, followed her lead. The Second World War had begun.

|

Moscow Non-Aggression Pact, 23rd August 1939

|

|