Britain in the 1930s

Introduction

The Great Depression

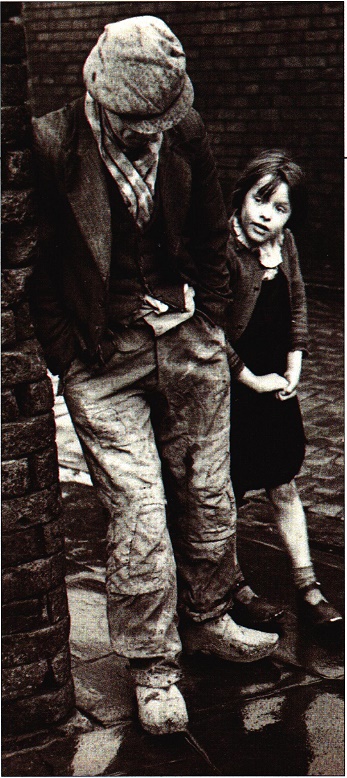

The worldwide 'Great Depression' of the 1930s, sometimes called 'the Slump', hit Britain hard. The heavy industries (coal, steel and shipbuilding) were worst hit. By 1931 nearly three million people were unemployed. Wales, Scotland and the north of England became 'distressed areas'.

Many young people were angry at the poverty and unfairness. Writers such as the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas criticised the government and tried to shock their readers. In 1936, Thomas wrote a short story about an imaginary Welsh village which he called Llareggub. Work out what it spells backwards.

In 1936, 200 men from the impoverished town of Jarrow marched to London with a petition asking for help; the government refused to speak to them or even to receive the petition.

Many people turned to Communism. Others, however, joined the British Union of Fascists (formed by Oswald Mosley in 1932), which was modelled on Mussolini's Italian Fascists. By 1934 the BUF had 20,000 members. At huge rallies, they gave the Nazi salute and chanted Mosley' and 'Down with the Jews!' Mosley's `blackshirts' beat up hecklers and threw them out.

After you have studied this webpage, answer the question sheet by clicking on the 'Time to Work' icon at the top of the page.

In 1931 unemployment benefit for a family with two

children was £1 10s

![]()

(half of what was regarded as an

adequate wage for a working man). This money was

stopped after 26 weeks; after that, families had to

apply to a Public Assistance Committee. They had to

take the hated 'means test' to make sure they had

nothing that could be used to raise money – for

example, people with a piano had to sell it. Many

unemployed people lost all hope.

Links:

The following websites will help you research further:

The 1930s:

• a powerful Dylan Thomas poem from a government propaganda film of 1942:

Wales - Green Mountain, Black Mountain

1. An extract from Louis MacNeice, Bagpipe Music (1938)

This poem rejects everything that the government does to try to improve life, and everything people do to make their life seem worthwhile – it's all 'no go'.

John MacDonald found a corpse, put it under the sofa,

Waited till it came to life and hit it with a poker.

Kept its bones for dumb-bells to use when he was fifty.

Sold its eyes for souvenirs, sold its blood for whisky...

It's no go the Herring Board, it's no go the Bible.

All we want is a packet of fags when our hands are idle.

It's no go the picture palace, it's no go the stadium,

It's no go the country cottage with a pot of pink geraniums.

It's no go the government grants, it's no go the elections,

Sit on your arse for fifty years and hang your hat on a pension.

Introduction (continued)

The Battle of Cable Street

On 4 October 1936 the British Union of Fascists planned a march through the East End of London. The area was full of poor Jews and Communist dockers. A crowd of a quarter of a million people gathered, determined to stop the march by blocking the route. As one man remembered later:

There was a forest of banners, and one stands out in my mind. 'They Shall Not Pass.' I remember, though I didn't really understand, that this is why I had come out with my fellow Jews, that the Fascists would not pass in East London.

Most of the fighting that day occurred between the crowd and the police, who were trying to make a way for the Fascists to march. While the Fascists waited, the police first tried to force a path through the crowd. They failed. The people were too densely packed.

Next, the police tried to clear a way down Cable Street, a side road. What happened there is known as the battle of Cable Street. The inhabitants dragged furniture into the road and built barncades. They pulled up the cobblestones to use as missiles. Jews fought beside dockers. Women threw milk bottles from upstairs windows. And they won. Some pohcemen simply surrendered. The police could not force a way through.

Instead, the Fascists marched into the centre of London. As they went, they pasted up posters saying, 'Kill the Dirty Jews'. Next day, they returned to the East End and smashed the Jews' shop windows in the Mile End Road.

In November, the government gave the police the right to ban political marches. The battle of Cable Street marked the end of Fascism in Britain. As one historian has written:

Cable Street was one of the punctuation marks of our times, for it was there that the Londoners looked Fascism in the eye, and said No.

J Cameron, Yesterday's Witness (1979)