King Stephen – when things go wrong

Introduction

King Henry I did not have a son to succeed him, so in 1126 he made his barons swear an oath to support his daughter Matilda. They all agreed, including Stephen of Blois (a particularly chivalrous and popular nobleman) ... but when Henry died in 1135, Stephen (supported by most of the barons ) seized the royal treasury and declared himself king.

Before long, however, Stephen's reign started to fall apart:

• In 1136-38, Matilda's husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, invaded and laid waste much of Normandy

• The Welsh rebelled in 1137

• In the north of England, King David of Scotland invaded and – although he was stopped at the Battle of the Standard in North Yorkshire (1138) – Stephen gave him Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmoreland to make peace.

These setbacks were disastrous – in those days, one of the main tasks of a king was to defend his kingdom, so this was a #massivefail for Stephen. In 1138, Stephen was further weakened when he quarrelled with the Church, arresting three powerful bishops.

Then, in 1139, Matilda, helped by her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, and by Ranulf, Earl of Chester, invaded England. In February 1141, at the battle of Lincoln, her forces defeated, captured and imprisoned Stephen; she took the title 'Lady of the English' ready to be crowned Queen, and it seemed that Stephen's reign had ended in disaster.

Before the end of July, however, Stephen's wife had organised a counter-revolution. Helped by the Londoners (who were, we are told, angered by Matilda's arrogance and bossy ways) she dislodged Matilda and rescued her husband, who was crowned king for the second time on Christmas Day, 1141.

Matilda continued, however, to fight for the throne; after 1152 her son Henry took up the fight. The civil war continued for another 12 years. Local lords took the law into their own hands – ALL the chronicles of the time say that it was an terrible time of slaughter, torture and robbery.

Then, in August 1153, Stephen's son Eustace died. In November, Stephen agreed the Peace of Winchester with Henry, which said that Stephen would stay king until he died, but that the throne would then pass to Henry ... which is what happened on Stephen's death next year, when Henry became King Henry II.

Study this webpage, then answer the question sheet by clicking on the 'Time to Work' icon at the top of the page.

Links:

The following websites will help you research further:

The Reign of

Stephen:

• Short biography on the

BBC website

•

Our Island Story - a narrative story account by the children's writer, HE Marshall (1905)

•

YouTube clip from the History File series

1 When Christ and his saints slept

This was written by the English monk who wrote the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

When the traitors understood that Stephen was a mild man, soft and good, who did not enforce justice, then did they all ... forget their loyalty; for every rich man built his castles, which they held against him: and they filled the land full of castles. They cruelly oppressed the wretched men of the land with castle-works; and when the castles were made, they filled them with devils and evil men. They took those whom they supposed to have any goods, and threw them into prison for their gold and silver, and inflicted on them unutterable tortures... They tied knotted strings about their heads, and twisted them till the pain went into their brains. They put them into dungeons, wherein were adders, and snakes, and toads; and so destroyed them....

They made towns pay protection money, and when the wretched men had no more to give, then they plundered and burned all the towns... Then was corn dear, and meat, and cheese, and butter; for there was none in the land. Men starved of hunger. Never was there more wretchedness in the land; nor did heathen men ever do worse than they: for they spared neither church nor churchyard...

The earth bare no corn, for the land was all laid waste by such deeds; and people said openly, that Christ and his saints slept. Such things, and more than we can say, we suffered nineteen winters for our sins.

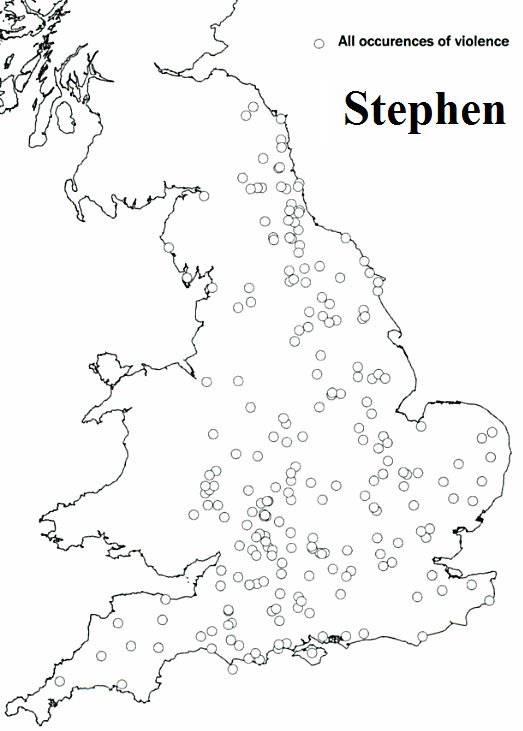

2 Violent incidents in England, 1135-54

Recently, some historians have suggested that the chroniclers exaggerated the 'anarchy' of 1135-54.

To challenge this idea, the modern historian Hugh M Thomas has marked on the map on the right all the incidents of significant violence recorded for Stephen's reign and, for comparison, all the incidents of significant violence recorded in the reign of Henry I (1100-35).

Interpretations

Historians do not agree about why government collapsed in the reign of Stephen.

Writers of the time all agreed that Stephen was a poor king – the 11th century historian Walter Map declared him 'a fine knight, but in other respects almost a fool' – and this was mostly the verdict right through the 1960s ... that the problems of the reign were Stephen's fault. It is still the verdict of many historians today.

Some historians, however, have suggested other reasons why the country collapsed into anarchy the way it did.

The historian RHC Davis has traced a complicated network of alliances and personal emnities between the barons – which seems to put at least some of the blame on 'over-mighty barons', rather than the king (although Davis himself considered Stephen a weak, treacherous man).

Many historians, also, have seen the reign of Stephen as a time of change in the feudal system. Government at the time of the Norman Conquest, they say, was 'personal lordship', granted by the king, based on personal loyalty to the king. By contrast, government by the end of the 13th century was based on institutions and laws and contracts. The 12th century, some historians have suggested, was the time when one system was evolving into the other, and these changes led to conflicts between the king and his barons – who were demanding that their lands and powers belonged to them, and were not merely gifts which they held at the king's pleasure.

3 Why Stephen lost control

This was written by the British historian RJA White in A Short History of England (1967):

Stephen's reign showed the vital importance of a strong and decisive personality on the throne in an age when feudalism could easily become another name for feuding...

The Norman barons gave their support to the mild and easy-going Stephen, who gave away a lot of crown land and relaxed the tight rein of his predecessor to get their support. Thus he began his reign on the wrong foot, and, as was usual in those days, he never got on to the right one.

4 The Treaty of Winchester, 1153

This was written by Robert de Torigni, a Norman monk, diplomat and chronicler, and friend of Henry II.

King Stephen recognised the hereditary right of Duke Henry to the kingdom of England, and Henry graciously conceded that the king should hold the kingdom all his life, if he wished, provided that the king, the bishops and the nobles should declare on oath that, after the death of the king, Henry should have the kingdom...

An oath was also taken that those lands which had fallen into the hands of intruders should be restored to their ancient and lawful possessors.