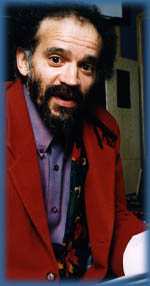

John Agard

- An Interview

John Agard

- An Interview

Poet John Agard came to the BBC

from London's South Bank Centre, where his unofficial title was

'poet-in-residence-at-the bar'. As the BBC's poet in residence he has

had a key role in Windrush, the BBC season of programmes marking the

50th anniversary of of the first major wave of West Indian immigrants

to the British Isles. Caribbean-born Agard's poetry is steeped in the

rhythms of the West Indies - a special mixture of African and European

styles. As he said on his appointment, he hopes to persuade programme

makers to include poems in cookery and gardening programmes. He also

makes himself available to BBC staff for poetic guidance, during a

six-month tenure funded by the Poetry Society.

How did you start to write poetry?

My earliest poetry and poems were written when I was about 16, in the

sixth form back in Guyana. But your love of language goes further

back. You don't realise these things until you look back at all the

things you love. At school my favourite subjects were English, French,

Latin. I loved taking part in school plays and debates. I went to a

Roman Catholic school and most of my teachers were priests. I was an

altar boy and we had to say the Mass in Latin. I used to love draping

myself in a sheet and pretending I was a priest. It was the

incantatory quality of language that I was responding to. Call and

response. Lord have mercy upon us, Lord have mercy upon us. Call and

response. Another thing was cricket, which was a very big thing in the

West Indies. You would hear John Arlott, this voice coming out of the

radio. I used to love the language - 'There's a breeze blowing across

the green carpet, and the batsmen take to the middle. The bowler

running up to bowl, rubbing the ball upon his flannels, the batsmen

cracks it majestically.' I realised I was responding to the language

in the same way I responded to the Liturgy.

What was your first poem?

I can't recall my first poem, but an early one was about a schoolboy

in the classroom thinking about how he had to take his exams. I really

hadn't studied for the exams so I was playing around, and I began

writing a poem. I was about 16.

Who is your favourite poet?

I don't know how people can answer that question because there are so

many great poets who feed so many things into you. I can't think of

one particular poet who will feed all those strands of you. I get

different qualities from different cultures. But yes, there are some

great poets - no one would question the fact that Ted Hughes was a

great poet, for example.

When did you leave the Caribbean for Britain?

As you know I grew up in Guyana. I left school in 1967, and went

straight into teaching. I taught the very subjects which I did for my

A level: French, English and Latin. As a 'pupil teacher' you didn't

have to be qualified. This was the late 60s. After a year of that I

worked in the library in Georgetown, the capital city. Then I worked

as a subeditor and wrote features on the newspapers. But my interest

was in poetry, and eventually I had two books of poetry published in

Guyana. Then in 1977 I left, because among other reasons my father had

settled in London. I was in my late 20s. But my childhood in Guyana

formed my consciousness. It is part of my mental landscape.

Can you give us an example of a poem that was influenced by

your early life?

A poem like the Woodpecker reflects something of the rhythms of my

Caribbean background. I try to get the voice of the woodpecker

pecking.

Carving

tap/tap

music

out of

tap/tap

tree trunk

keep me

busy

whole day

tap/tap

long

What words of advice would you have for a budding, unpublished

poet?

In the first place it's important to realise it's not easy getting

poetry accepted. There is no point deluding you. But when you have

that desire to create poetry, you become a vessel of the muse, and you

are creating because there is that inner desire and compulsion to

create. Getting published is a test of commitment. I would recommend

keeping a notebook with your poems so you can see the changes of the

poem, rather than just creating it straight off on the computer. It is

nice to see the organic stages the poem went through, and you can see

the choices that you made: why did you use this word instead of that,

why did you scratch out this or that word? Also you should read

nursery rhymes, or better yet, say them aloud, get right back to the

incantatory source of language, poems from oral cultures, Celtic

charms, Yoruba, Eskimo, Native American poetry. Also fairy tales and

mythology, folk tales of the world. You are equipping yourself with a

great resonance. You are feeding your inner poetic cupboard, so when

it comes out your work will have a resonance.

(From the BBC Online site)